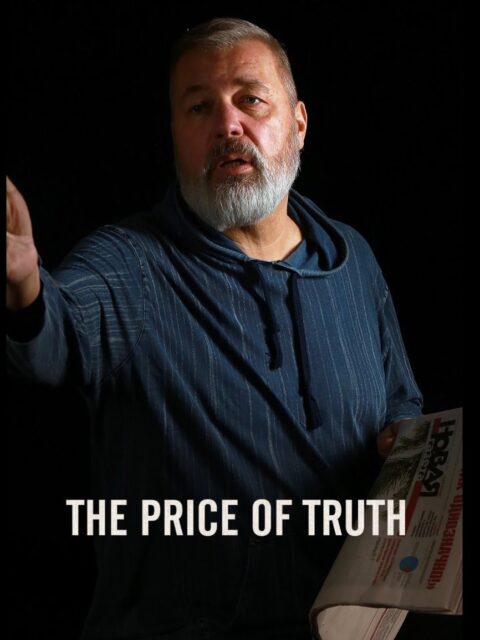

New documentary shows ‘The Price of Truth’ in Putin’s Russia

The film follows Nobel Prize-winning Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov as he tries to keep the country’s last independent newspaper in operation.

Aboard a train leaving Moscow in April 2022, Nobel Prize-winning Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov was doused in red paint laced with acetone, damaging his eyesight.

As the editor-in-chief of Russia’s last independent newspaper, Novaya Gazeta, Muratov is no stranger to the consequences of printing the truth in Vladimir Putin’s autocratic Russia: his paper has seen six journalists murdered since its inception in 1993. The Price of Truth, a documentary directed by Patrick Forbes, follows Muratov as he endeavored to keep the paper in operation after Russia invaded Ukraine. The newspaper suspended operations in Russia in March 2022, citing “military censorship,” and was ultimately stripped of its Russian media license in September 2022.

ICIJ interviewed Forbes about press freedom and Muratov’s fight to print the truth in a country where journalists are constantly under threat. The film is part of the Double Exposure Investigative Film Festival and Symposium, a forum dedicated to highlighting investigative journalism through a visual lens.

You’ve been friends with Dmitry Muratov for decades. Tell me about him. What inspired you to center this documentary around him?

As soon as I knew he was getting the Nobel Peace Prize, I rang him up and said, “come on Dimur, let’s do a documentary about you.” And he laughed and said, “a film about me?” And he asked exactly that question, why about me?

The answer is that I could see immediately that there was going to be some sort of headlong collision between him and Vladimir Putin. The two men stand for completely different visions of Russia; on one hand there is freedom and freedom of speech and on the other hand is control, repression and autocracy.

I knew that as we watched over the year, the two men would come into conflict. My hope, which hasn’t come to pass, is that Dmitry and his values would eventually triumph.

As a person, Dmitry is ridiculously brave. He is decent and he is a man of principle. I also know that he had a fearsome appetite for alcohol, which I discovered when first I met him.

Can you tell us more about this first meeting?

In the early 2000s, Moscow was this extraordinary place. It was the wild East, and I’d just been filming Britain’s The National Trust [a BBC series], about a heritage organization, and to my surprise they had been really difficult to deal with. So I thought, if I’m going to be lied to, I might as well be lied to by the biggest liars in the world. And those were the oligarchs, the wealthy billionaires of the newly capitalist Russia. So I thought, there’s an interesting problem.

It was my second or third visit to Russia and the oligarchs, surrounded by the best PR that money could buy, were giving us the runaround. I asked my fixer how to get some truth in this situation and she connected me to Dmitry. We went to Novaya Gazeta, the newspaper he edited. After waiting for him to turn up — he is always late — we heard a shout, asking, do we drink? And a whisky bottle slammed down on the desk. “Now we drink, and talk,” he said. Two things became immediately apparent. One, he did know what he was talking about, and two, he was indeed, going to tell us the truth.

I was completely drunk by the end of the first meeting. On whisky, which I don’t even like.

At the moment, he’s not drinking anymore. He’s not drinking until the war is over.

The film shows Dmitry shortly after he’s been attacked with red paint and acetone on a train in Russia, damaging his eyes and eyelids. How does that shape the documentary?

What I had foreseen was happening: the clash between Dmitry and Putin’s government was taking place. By that time, we had been filming for a month or so and Dmitry was quite fed up with his inability to affect the course of the war. So he decided to auction his Nobel Peace Prize. Days after saying that, he is on a train on his way to visit his mother for her birthday, and a door swings open and this guy douses him with red paint laced with acetone, which cost him part of his eyesight.

But, Dmitry being Dmitry, he refused to give in to the apparent message, which is clearly “you shut up and keep your newspaper quiet.”

He refused to pay any heed to that and kept his newspaper open. He went to see his mother, despite the pleas of his staff to see a doctor.

Press freedom in Russia had been deteriorating before production began. Six of Muratov’s journalists have been murdered since the paper’s inception in 1993. What did filming in Russia feel like under those conditions?

Incredibly dangerous. The immediate concern was that not only were we placing his staff in danger every time we filmed, but also our filming crew. Every time we filmed, we weighed whether or not it was safe to do so and whether or not it would endanger the staff or the team.

I’ve never done a film like it but I felt that it was very important that we do so because I wanted to show the world that there are Russians who oppose the war. It’s not, as often perceived, one nation behind Putin. The reverse is true. The war is incredibly controversial inside Russia and the sadness is that the Kremlin has such control over the media that this never seeps out.

I would say somewhere between a quarter and half of Russians don’t support the war, and Dmitry remains their effective mouthpiece. And long may he remain so.

Can you talk about some of the risks that are involved if journalists or citizens don’t follow the Kremlin’s media rules?

It’s incredibly dangerous and incredibly arbitrary. Those of us who live in Western democracies don’t appreciate just how terrifying the day-to-day situation is in countries like Russia. You can wake up one day as a free woman and the next in jail because of something you said or something your friends said. And you have no warning. It’s really, really alarming. The strain it puts people under is immense.

One of the toughest conversations we had making the movie was with the crew who’d worked on it, who had filmed inside and outside Russia. I said, “Look, do you really want your name on it?” Expecting the answer to be no. And to their eternal credit, they said “absolutely, we want our names on it. We want to say that we did this.” And some of them are still living inside Russia, some of them have family living inside Russia. I was very moved by their courage.

Can you talk about the logistics and safety planning of filming?

Nice question, but I can’t talk about it. Suffice to say, I don’t normally film backed by a 50-page document every time we move.

Muratov refused to answer questions about his safety while filming. Can you speak to why he made that decision?

I think for two reasons. First of all, safety is a moment-to-moment concern for him and his team. Second, he feels the loss of the six journalists acutely. His concern for his staff and his guilt over the loss of those six people, I think it’s almost the defining mark of his life, actually. It’s with him every moment of every day. I think he did not want to demean their memory by talking about it but equally, it’s just integral to his day to day existence.

Truly brave people don’t make a big deal about it. They just sort of get on with their lives … They don’t want to celebrate it or talk about it.

There’s also the fact that truly brave people don’t make a big deal about it. They just sort of get on with their lives. The people who aren’t truly brave, they tell you stories about how they did something extraordinary, etc. The brave are almost unaware of their bravery. They don’t want to celebrate it or talk about it, they just want to move on and do the things they do.

In Dmitry’s case, the fight against Putin is so all consuming. So he isn’t going to talk about being scared or worried because if he ever admitted those things, I think it would become impossible.

The essence of my film, I began to realize, was a man who risked his life every time he went home, which is the opposite of the rest of us.

Muratov agreed to do this film as long as it didn’t endanger his journalists or staff. It’s one thing to plan for safety during filming but do you think the project’s release ultimately puts them at greater risk?

Obviously you’re worried about what the impact will be once it’s out. One of the first things I did, which is quite unusual for me, is I showed Dmitry the film before we premiered it in a theater because you can take part in a film but not really be aware of the collective impact. He was very resistant to being shown the film because he felt it wasn’t journalistically right. I said, “look, the reason I want to show you is that I want you to see it and be aware of the risks it may pose to you and any of your team, if indeed it does.”

At the end of it, which was very emotional, he and his wife were visibly moved. They just said, “great, show it.” And he has not deviated from that attitude.

What does Muratov and his now shuttered newspaper, Novaya Gazeta, mean to the Russian public versus what it represents to the international community and others abroad?

I guess it could be very easy to be an outsider going “aren’t they great, aren’t they brave, aren’t they wonderful” and then insiders going “oh they’re just an irritant, they aren’t as great as you think.” Actually I think the reverse is true. There is an immense respect inside of Russia for what they do and I think that’s oddly part of the reason why the state has taken a very long time to move against him. Looking at what he does and stands for, you would have expected him to be in trouble earlier than he has been, and that is interesting.

That respect has been built up over time. It’s actually a testament to the power of investigative reporting and the fact that the paper isn’t an empty set of values. For example, they don’t rake over people’s private lives. They concern themselves with serious issues and have done so bravely for 30 years. Was it popular initially to reveal that the Chechen war was being waged politically and that people were being killed in a manner that they absolutely should not be killed? No, it was not. And Russians didn’t want to hear it, but hear it they did. And eventually people thought, that’s not right.

Likewise, the billions stolen by rich people around the Kremlin; was that popular with the government? Absolutely not. Was it accurate stuff? Yep. Did some behavior change? Yes.

Obviously Russians will not be able to see this film through state media, but will they get a chance to view it through other means?

How much is this film in circulation inside Russia? Well, if I did know, I couldn’t tell you. Every film of mine has been reliably ripped off and shown inside of Russia. This is one where I’m hoping!

In your opinion, what is the future of press freedom in Russia?

There is always hope, but at the moment I think that hope is outweighed by fear. I think that the future, at least the next couple of years, looks very bleak unless there is a challenge to the current regime, and I don’t see that happening anytime soon. I think it’s going to remain a very dark situation for press freedom in Russia.

That said, the Russian journalists I meet are immensely brave and they are not giving up. Dmitry is certainly not giving up and I think our only hope is if people like him continue to fight for something so important. And I hope to God that they win, eventually.

How does that lack of press freedom stand to affect the rest of the world?

It is incredibly corrosive. I think the standard that has been set in Russia and followed elsewhere is one of the worst, if not the most frightening trend of the last 20 years. The creation of strong man governments following Putin’s regime has had appalling consequences for the world. Because of the creation of those governments, dotted across the globe, journalists’ freedom, and the ability to say the truth, has never been more tenuous.

Following Dmitry’s lead, I think it’s only by speaking truth to power that you can stop terrible things. If there is no freedom to point out abuses in society, then those abuses will persist and regimes will do terrible things, including going to war when they should not.

Tickets are on sale now for the Double Exposure Investigative Film Festival and Symposium in Washington, D.C., Nov. 2-5, 2023, presented by 100Reporters.