On Dec. 12, 2007, billionaire Igor Olenicoff pleaded guilty to filing a false tax return that helped him conceal roughly $200 million in offshore holdings, stashed mainly in the Bahamas, out of U.S. tax collectors’ reach. Caught up in one of the highest-profile tax evasion cases in recent history, Olenicoff faced the prospect of joining other top-dollar tax cheats who have found themselves behind bars for defrauding the Internal Revenue Service.

But, when Olenicoff appeared for sentencing the following April, jail time wasn’t an issue: He had won over the judge.

“You are an incredible man,” Judge Cormac Carney told Olenicoff after reading a binder filled with positive information about the billionaire. “You’re probably the smartest person in this courtroom. You have tremendous common sense.”

Moments later, the California federal court judge would hand down a punishment to the billionaire that would become notable for its mercy. Having agreed to pay $52 million in civil fines and back taxes to the IRS, Olenicoff walked out of the courtroom a free man: he would be on probation for two years and required to perform 120 hours of community service.

Given the staggering sums of money he had hidden and the long-running federal pursuit of his offshore holdings, Olenicoff’s avoidance of jail time awed some commentators. Forbes marveled at the light sanction and in another article pronounced that Olenicoff had received a “sweet deal.” Olenicoff himself described his sentence as “an excellent outcome.”

It was so excellent, in fact, that the case set a precedent for other billionaires to claim they should also avoid imprisonment for charges of large-scale tax evasion.

Olenicoff’s success was aided by the law firm representing him, the venerated Beverly Hills-based Hochman Salkin Rettig Toscher & Perez.

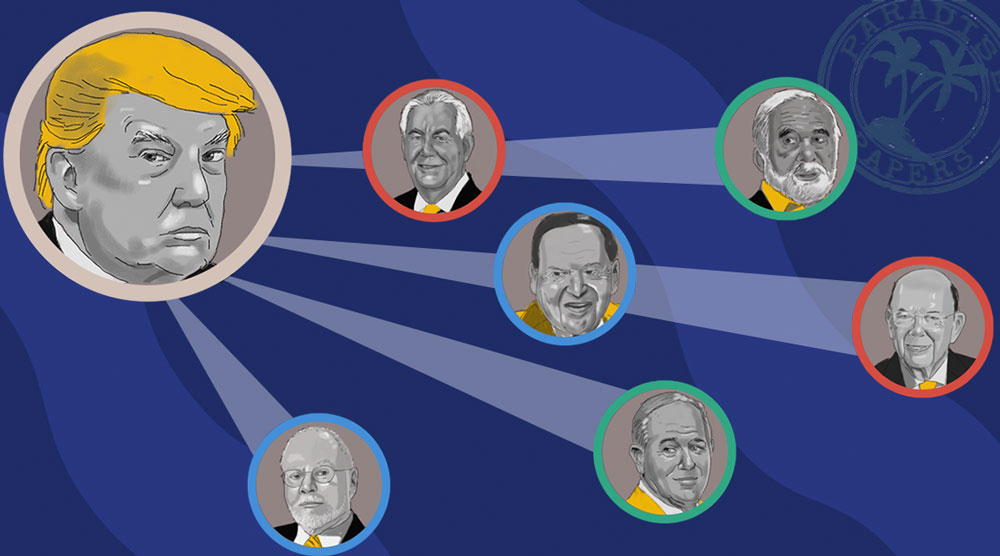

In recent weeks, the firm has received renewed attention: President Donald Trump recently announced his intent to nominate one of the firm’s partners, Charles Rettig, as the next commissioner to lead the IRS.

Rettig did not personally represent Olenicoff, but for the past 35 years, Rettig has based his career largely on representing clients against tax collectors, offering his extensive expertise to wealthy people seeking serious firepower against government actions.

At the same time, Rettig is far from a single-minded crusader against the IRS: While he has represented the wealthy in tax proceedings, he and his firm also have advised the IRS and state tax agencies on how to be more effective. Rettig has even served a stint as chairman of the IRS Advisory Council. In public remarks, Rettig has spoken of federal tax collectors with admiration.

Though they defend clients with offshore holdings, neither Rettig nor the firm participate in creating or administering tax shelters, according to law partner, Steven Toscher. Indeed, a search of tens of millions of leaked documents from offshore jurisdictions contained in ICIJ’s various databases, including the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers, found nothing of note and no correspondences relating to the nominee or his law firm.

If confirmed by a Senate, Rettig will be tasked with implementing President Trump’s sweeping tax overhaul in an agency struggling with years of budget and staffing reductions. The IRS has lost thousands of agents, and overwhelmed officials have struggled to collect money the IRS has calculated it is owed.

While Rettig’s background is varied, one thing is certain: the IRS nominee has considerable expertise in federal attempts to collect revenue from offshore accounts often designed to keep the money out of reach.

In recent years, with input from Rettig’s firm, the IRS launched a high-profile series of efforts to pressure Americans to come clean about hidden offshore holdings, including bank accounts, trusts and shell companies that the wealthy have used to dodge taxes. These programs, generally known as voluntary compliance programs, offer benefits for coming forward – and warnings of criminal penalties for those who don’t – to encourage disclosure.

In addition to taking on the Olenicoff case, Rettig’s firm has also represented clients facing government scrutiny for a tax shelter known as SC2. This maneuver was set up by accounting firm KPMG and has been described as improperly classifying for-profit investments as contributions to charities. The SC2 was among the main subjects of a 2003 Senate subcommittee investigation on tax shelters, and the panel’s chairman, Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., called the maneuver a “sham.” The following year, the IRS added SC2 to a list of abusive tax transactions. (It has remained there since.) But Rettig publicly defended his clients’ use of the embattled tax shelter, using an argument familiar to tax enforcement authorities: The maneuver had been technically legal.

“The SC2 transaction is not the poster child for abusive tax shelters that the government would portray,” Rettig told the Los Angeles Times during the SC2 controversy in 2005. “The tax result may be highly objectionable to the IRS. But as a technical matter, many knowledgeable practitioners are convinced it will be upheld in litigation.”

Comments like this worry critics, who question whether his allegiances lie with the tax agency or those seeking to dodge its reach.

“Rettig’s sympathy for rich people seeking creative solutions to minimize their tax obligations makes him a poor choice for a country experiencing massive economic inequality and a declining ability to collect owed taxes from the economic elite,” said Jeff Hauser, executive director of the Revolving Door Project, a nonprofit group that seeks to increase scrutiny of executive branch appointments, in an email to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

For those linked to the Panama Papers, there are likely a thousand explanations … and for some, sleepless nights ahead.

Rettig’s law partner Toscher told ICIJ that such criticism of Rettig was unfounded. “He has long espoused accountability for those who don’t voluntarily comply with their filing and reporting obligations and has participated in training sessions significantly improving the examination functions of IRS employees as well as their state counterparts,” Toscher said in an email. (Rettig did not respond to a request for an interview; Toscher answered questions ICIJ sent to Rettig.)

“At the request of the IRS and California taxing authorities, Chuck [Rettig] has also long served on their advisory boards providing invaluable advice for the proper, efficient and effective administration of our tax laws,” Toscher added.

Citing the law firm’s policy, Toscher would not comment on the Olenicoff case except to note that public records confirm that Rettig did not personally represent the billionaire.

Rettig has written extensively for Forbes’s website and other publications about how the wealthy should handle offshore holdings, commonly encouraging readers to immediately take steps to report any illicit accounts to the IRS.

In response to ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation, Rettig wrote an article pointing to the potential for future leaks and whistleblowing to urge readers to begin reporting their offshore holdings. “For those linked to the Panama Papers, there are likely a thousand explanations … and for some, sleepless nights ahead,” he concluded.

Responding to a question of how Rettig would help the IRS more effectively bring offshore accounts out of the shadows, Toscher argued the agency should make the process easier for taxpayers.

“Efforts should be made at simplification and reducing the burden of reporting,” Toscher said of offshore accounts. “It is a difficult challenge – but simplification, taxpayer education and assistance and ease of compliance will help achieve greater compliance.”

Toscher said that Rettig’s experience with both private and government practice positions him to improve IRS offshore enforcement.

Speaking in 2016 at a conference about offshore tax compliance, Rettig said he saw few differences between private and public service.

“But for those of you who practice in this arena, I think you’ll quickly get onboard with the concept that there really is not a distinction between government and private practitioner,” Rettig said, according to a transcript of the speech. “We’re all in the same business, which is trying to get people, who for whatever reason are not in compliance, back into compliance.”

Rettig then added a key caveat: “The only distinction is the private practitioner likes to get there before the government” and help get the client on a road toward compliance to improve the chance of a better outcome.