MEET THE INVESTIGATORS

Secrecy, intimidation, and cracking the ‘iron wall’ around Cuba

In this month’s Meet the Investigators, Barbara Maseda tells of the challenges of finding data and documents in Cuba, a country where journalists are threatened and harassed and where information is kept hidden away.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists collaborates with hundreds of members across the world. Each of these journalists is among the best in his or her country and many have won national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

This month we speak with reporter Barbara Maseda, who is the director and founder of Proyecto Inventario, an open data initiative that helps journalists to find data and documents to support their reporting in Cuba, a country without transparency policies and with very poor internet access. Barbara shares valuable insights into what’s happening behind the “iron wall” that the regime has built around itself, and tells us that even though authorities actively intimidate Cuban journalists — even threatening their families — she believes it’s because the government is afraid of the power of their reporting.

ICIJ’s Meet the Investigators series was recently awarded by the American Journalism Online Awards as the feature “most likely to inspire young journalists.” Thanks to all our ICIJ Members who have shared their stories with us, and to the community of ICIJ Insiders who have supported this work.

Sean McGoey: Welcome back to the Meet the Investigators podcast from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. I’m your host, Sean McGoey, and I’m an editorial fellow here at ICIJ. This month, my guest is a journalist whose mission is to ensure that vital information is actually available to the public, even when the government tries to prevent that from happening.

Barbara Maseda: My name is Barbara Maseda. I’m a Cuban journalist. And I run a project called Inventario that works with data and information that is very hard to come by in a country as closed as Cuba.

McGoey: Here’s the rest of my interview with Barbara Maseda. What made you want to become an investigative journalist?

Maseda: When you grow up in a country where everything is a secret, it’s not very hard to want to uncover those types of truths that are not out there for you to get to know. When you see what our peers are accomplishing in other parts of the world, you wonder why you don’t have that in your country. And it makes you want to have that for your country, for your people.

McGoey: What are some of the challenges that journalists face trying to do their job in Cuba?

Maseda: What we had was this iron wall that was keeping the island completely isolated in terms of information from the outside world. This absolute control that the government used to have makes it very hard for journalists to have access to the bread and butter of our profession — sources who are going to give you information.

For starters, independent journalism that is not controlled by the government is illegal. You cannot register a news organization. You’re not going to be acknowledged as a reporter who wants access to a source. And if you have a whistleblower in another country, we do not have the culture or history or the condition for the emergence of this particular type of individual, who is going to give you access to something that you’re going to follow and turn into stories.

There are other countries where authoritarian regimes have a very tight grip [on] many things and treat journalists in a similar way. But I think that in the case of Cuba, it’s that the system is very cohesive, and there are no cracks in that system — or we’re starting to see some of those cracks now. It’s a problem that I think has been changing in the last few years with the emergence of the internet.

McGoey: So given those conditions that you describe, what was it like to study journalism in a country that seems to be fairly hostile to the profession?

Maseda: I did my undergraduate degree at the University of Havana, [in] the school of communication. So my degree officially says that I have a bachelor’s in journalism from a Cuban university.

But — and this happens a lot in the Cuban space — we have labels or terms that mean something very different outside of Cuba. So when you go to the school of journalism, you would expect the standard reporting skills that you learn anywhere else. And what really happens is that nobody ever tells you that your role as a journalist is to hold the Communist Party to account.

It’s the contrary, actually. You are trained to be a watchdog, but for the interests of the establishment. And if you never question any of that training, you’re gonna keep doing something for the rest of your life that is labeled as journalism, but that in practice is not working in the public interest — is not work that is holding the powerful to account.

What many people do, is you go outside of the Cuban borders and you try to get some training, or you try to get inspired by the work of others. After you spend so much time isolated, getting exposed to that kind of work can be really powerful.

McGoey: Barbara’s background in science attracted her to data journalism, so she followed that well-worn path and left Cuba to get a master’s degree in the United Kingdom, where she learned the technical skills to mine text from social media posts and collections of documents.

You went back to Cuba after your master’s. How did you ultimately decide to leave again?

Maseda: The problem was that when I went back to Cuba, with all the knowledge that I thought was the solution to my problems, I encountered many other problems — mainly, the lack of internet access was a big obstacle for anything I was trying to do.

At the time, you could not go to a company and hire internet service for your house. So when I was doing this, the way for Cubans to access the internet was public parks, where there was public Wi-Fi. The first thing you realize is that you have no power plugs in public parks. So it’s not only that it’s harder for you to work under the tropical sun in the Caribbean. It’s also that you also have to hurry up because your battery is going to die really, really soon.

It’s not by chance. The system is designed in a way to make the work of journalists in general — and, of course, other professions that need this type of independence — really hard.

McGoey: So in 2017, Barbara left Cuba and moved to California for a Knight Foundation journalism fellowship at Stanford University.

Maseda: I started with part of the work that I had done in the master’s program, about my interest in turning text collections into structured data. I did that because I thought it was something that would give me a chance to find information that was newsworthy in the Cuban space.

My country does not have government websites where data about anything is published in a structured, open format. So maybe having the knowledge to process documents, maybe that would be a way to access information that can be processed in a way that will become more useful.

McGoey: But even though the fellowship was a great opportunity to learn about the technical aspects of data journalism from experts in the field, Barbara couldn’t stop thinking about the situation in Cuba.

Maseda: I think that many of us — when you leave the country and you see what you left behind — you have this feeling that you have to do something to help fix that situation. So I stopped working on this more technical project and I started designing what Inventario is today.

That’s one of the reasons I started it as a project that could be changing over time — because I was hoping to adapt to whatever reality we had in Cuba at the time. The way it started was thinking of these public parks where I had been, but in the years that I haven’t been there, there have been changes.

In a totalitarian regime like Cuba, you have to understand that information is something that can destroy the stability of the system. They’re not only incompatible — they mean mutual destruction.

Now Cubans have access to the internet in their phones — not everybody, because it’s a really expensive service, but some people do. So we are doing experiments with what people could be contributing from their phones, when you have citizen journalists around the country that could be reporting back to you.

McGoey: How difficult is it to get access to records in Cuba?

Maseda: It’s impossible. It is absolutely impossible. Because in a totalitarian regime like Cuba, you have to understand that information is something that can destroy the stability of the system. They’re not only incompatible — they mean mutual destruction.

First of all, we do not have a law in Cuba that warrants the access of journalists or citizens — or anyone — to public records. We do not have a public records law, like FOIA here in the U.S.

Also, the ministries of agriculture and transportation and all that — those organizations do not publish by their own will any type of records that you can access. This has been like that for many, many years.

I don’t think there is the political will to change any of that in a way that is going to benefit journalism. If anything, I have to say that what we’ve seen is that it is going backwards.

McGoey: How do you see it going backwards?

Maseda: In recent years, I remember that the website of Cuba’s Supreme Court started publishing a very basic dataset of the court cases and the lawyers — and this is new, this has never happened in Cuba. And then what happened is that they made changes to the website and they specifically deleted the database that they had made public for some reason.

I think that what happens is that they give you access to something [where] they’re not absolutely sure how much damage that could mean to them. But then they learn that people can find this, so the reaction to that is to cut access again.

It’s interesting for us, because in a way you can get an idea that they’re keeping it [the data]. There’s hope that at some point, we could access that type of information.

McGoey: Is the government actively harassing or threatening journalists for doing their work?

Maseda: Sometimes they try to make you work for them, in this sort of undercover position [where] you still pretend to be an independent journalist who’s reporting about the problems of the country, but in reality, you’re reporting back to [them].

But this is also a process where they’re assessing you. They’re studying if you’re going to cooperate with them or not, and once they realize you’re not, then you get a different type of treatment.

And this treatment consists [of] having someone standing outside of your door. And if you try to go out to go grocery shopping, or anything you want to do outside your house, they tell you that you cannot go out. This has happened to many of my colleagues recently. And this is a way to keep journalists arrested in their own houses. It’s like your house becomes a prison, and they keep you there. And there is no law or court order, or anything that backs any of this, but it’s the way it actually works on the ground.

And they threaten your family because many times it’s easier for them to put pressure on you through a relative, like your partner or your parents, based on this idea that it’s easier to sacrifice yourself than to sacrifice others. It’s pure evil.

But even in these conditions that are horrible, I think that the reason this is so bad right now is because they have seen how powerful this reporting can be against them. They have been portraying an image of the country that doesn’t really exist.

And they threaten your family because many times it’s easier for them to put pressure on you through a relative, like your partner or your parents … It’s pure evil.

McGoey: According to Barbara, another frequent form of retaliation by the Cuban government is cutting off internet access to dissident voices. In a twist almost too perfect to make up, on the day that we spoke, Barbara was going to attend a virtual press conference called by Cuban artist and activist Tania Bruguera, which was ultimately called off after Bruguera’s internet service was suspended.

It was against this backdrop that Inventario was born.

Maseda: We started as a data driven type of project. And we also have an interest in putting the topic of transparency and access to information in the public conversation. We try to uncover information and open datasets and make certain documents available. But the difference is that [for us], doing that is three or five times harder than it is for journalists somewhere else.

We are always among the last 10 places [for] press freedom in the world. So anything you try to do in the profession is going to be affected by this awareness we all have as citizens that this is illegal or disliked by power.

McGoey: Barbara also shared that one of the biggest hurdles in making Cuba’s information ecosystem more open comes not from the government, but from regular Cuban citizens.

Maseda: The simple fact that people are curious — and not taking for granted that information is not for them to see — is a big change in what Cuba was before. Of course, we get a lot of rejection also from people who do not understand why we want to have access to data.

The idea that you, as a citizen, should also be entitled to know what the government is doing with the public budget is something that is foreign still to people. We are, many times, attacked by the same people that we’re trying to help. And that is really discouraging. We’re used to it now, but it was very hard in the beginning.

McGoey: In addition to changing norms around citizens’ right to access public information, Inventario also shakes things up with a data-driven, highly visual approach to journalism that Barbara says is very different from what Cubans might be used to.

Maseda: We’re very interested in the power of visual investigation in Cuba because we have to work with what we have.

We come from this journalistic tradition that is more narrative. There are great projects in Cuban journalism today that rely a lot on beautiful uses of the Spanish language that I really enjoy. But what we’re trying to bring to the table is something new to serve a type of audience that has other ways to consume information — like a chart that communicates information fast or a visualization that shows you how a process works.

It’s an experiment in a way, but at the same time, we’re showing people something that many of them didn’t know they [liked].

McGoey: Earlier, you mentioned using contributions from people on the ground in Cuba. How has crowdsourcing information been crucial to Inventario’s success?

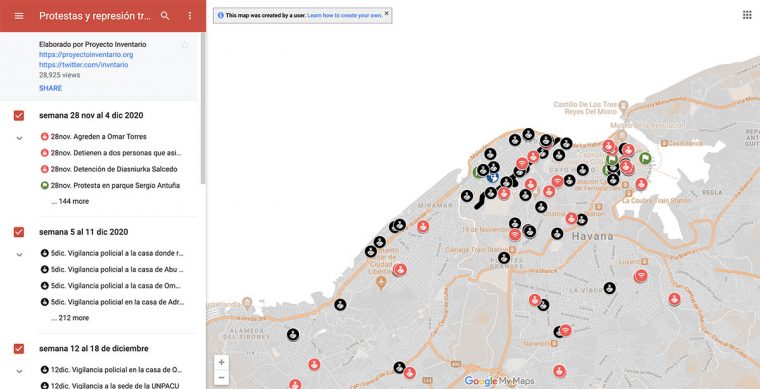

Maseda: We have been, for many months now, following on social media the information people share in pictures and video of police and state security forces harassing activists and journalists.

Something that has become common in Cuban social media that was nonexistent before is people recording the person, who is dressed as a civilian and is telling you that you have to go with them.

It’s sort of a kidnapping, because nobody’s showing you an ID that they’re officers of the law. They’re telling you that you have to come with them, and they put you in a car. And the car is not a police car many times. For the first time now, we have images of those cars and those people.

McGoey: Over the course of time, as patterns started to emerge, Barbara and her team were able to identify one particular vehicle whose presence indicated trouble for protesters and activists.

Maseda: Five or six months after the beginning of this work, we were able to find four instances of a bus — the same type of bus that is actually used for public transportation. We saw this car in different and very violent types of repression against groups of people. When you see it parked somewhere, something bad is going to happen.

Once we have a trend, we release it to the public, and then that becomes an invitation to people. And we asked for their help. Basically what we did was show this bus we have found that is used for this purpose [and ask] Please, if you see it anywhere else, we need more information about this. After that, people started actually sending pictures of the bus.

It’s amazing, because you can see that there is this collective conscience that we as citizens can have a lot of power if we put [our] forces together.

McGoey: Before we wrap up, I have one more question: What advice would you give aspiring journalists?

Don’t think of the practical use of anything and everything that you’re going to be learning, because there’s knowledge that you might not think is going to be useful — and then it is.

When I was doing the master’s in England, I would go to class, and class that day was about mining tweets. I wouldn’t see how that would be useful for me in a country where in 2015, nobody was using Twitter.

When I launched Inventario, Twitter was still not a thing. And a month after we launched, the Cuban president decided that it was important, so it was a big government decision that then turned Twitter into a very relevant platform. And there I was a month after launching, being the only [one of a] few people qualified to do that type of network analysis. So learn everything you can, even if you don’t know how it’s going to be useful, because it will be.

McGoey: Barbara, thank you so much for joining us!

Maseda: Thank you for having me.

McGoey: Thanks again to Barbara Maseda, and to all the journalists who share their stories on the Meet the Investigators podcast.

The show is a production of the International Consortium of investigative Journalists, and this episode was produced and edited by me, Sean McGoey, with help from Scilla Alecci.

We hope you’ll share this episode on social media using the hashtag #MeetTheInvestigators, and please send us your feedback at social@icij.org. Thanks for listening. Talk to you again soon!

If you’re a fan of our Meet the Investigators series, please consider making a donation to support ICIJ. Not only will your donation help support our work with journalists like Barbara, but as an ICIJ Insider, you’ll also receive sneak previews, access to exclusive chats with reporters and behind-the-scenes content like this delivered straight to your inbox. Donate today, and support independent investigative journalism.