The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has hundreds of members across the world. Typically, these journalists are the best in their country and have won many national and global awards. Our monthly series, Meet the Investigators, highlights the work of these tireless journalists.

Long before ICIJ delved into the vast bribery operation managed by the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht, two ICIJ members had been leading the way in investigating the company’s corruption.

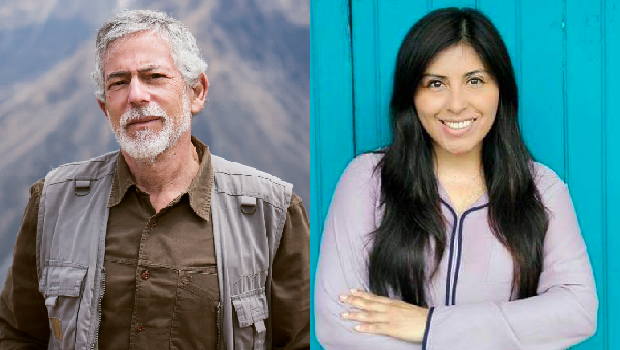

Gustavo Gorriti and Milagros Salazar, both from Peru, are leaders of major investigative journalism networks in Latin America. Gorriti’s IDL-Reporteros and Salazar’s Investigate Lava Jato network, which she co-coordinates with Flavio Ferreira of the newspaper Folha de Sao Paulo, have been covering the Odebrecht case for years. Salazar is also the director of the Peruvian investigative news site Convoca. Both Gorriti and Salazar manage international teams of reporters that have broken major stories about the scandal.

On June 26, Salazar and Gorriti were among more than 50 journalists across the Americas who launched the Bribery Division, a new ICIJ-led investigation revealing hundreds of millions of dollars in secret payments made by a unit of Odebrecht that was created primarily to manage the company’s bribes.

Bribery Division revelations have sparked resignations in the Dominican Republic and calls for further investigation from an influential U.S Senator, the attorney general’s office in Panama, and civil society groups across the region.

ICIJ spoke with Gorriti and Salazar about their experiences investigating Odebrecht, what it was like to work together on the Bribery Division, and what to expect next as the political shockwaves from Odebrecht continue to ripple across Latin America.

Can you describe your network and the reasons why you created it?

Milagros Salazar: The Investigate Lava Jato network is a network of investigative journalists in 15 countries in Latin America and Africa. We started because we could see that the Lava Jato case needed collaboration, and not only in terms of exchanging information about acts of corruption, payments of bribes, of hidden financing of political campaigns in our countries. It required that we become methodologically solid. [Editor’s Note: Operation Car Wash is an ongoing investigation by the Federal Police of Brazil, which began as a money-laundering probe and quickly expanded to examine corruption connected to Brazil’s state oil company, Petróleo Brasileiro S.A., or Petrobras, a multinational.]

When the Lava Jato case began in Brazil, we saw that there was very little investigative journalism. What we wanted was, in parallel to the daily coverage, to develop investigations in which we shared information, developed our own sources, built collaborative databases and traced the money. This would allow journalism to contribute in an important way to advance the investigations in our countries.

Gustavo Gorriti: IDL-Reporteros is one of the most long-standing digital outlets dedicated to investigative journalism. We started to operate at the end of 2009 and the first publication we did was in 2010. The reason we brought it into existence was that the only way to be able to do investigative journalism – without limitations, sustained, intense – was to create small newsrooms of this kind.

I did it after a long experience in traditional media, what you call legacy press. The limitations that existed were large, most of all on the business side, to bring forward investigative journalism that was sustained and sustainable. It was necessary, it was indispensable to have digital media dedicated to this.

Both of your networks have investigated Odebrecht in depth. Why is the Odebrecht case so important to Latin America and why did you decide to focus on this topic?

Gorriti: We started to work on the case in 2010, with a series of investigations into abnormalities that emerged into view: cost overruns of the projects, the fact that one group of companies won almost all the bids. We published some things but it was clear that the methodological difficulties to get to the bottom of the investigation were enormous.

In 2014, the Lava Jato case began in Brazil, and it advanced on what previous investigations had found. We saw that there was enormous potential in that investigation that transcended Brazil. We knew that what was happening in Brazil was happening in the rest of Latin America.

We also saw something else that was very important. In Brazil, the prosecutors, the judges and police had taken leadership of the investigation. In the rest of Latin America, it wasn’t going to be like that. There it needed to be investigative journalism. And there began a very interesting competition between those prosecutors, the small group of virtuoso prosecutors, and ourselves. That allowed the investigation to advance at great speed.

Salazar: As Gustavo has told you, in Peru it was journalism on the Lava Jato case that made it possible for the investigations to begin at the prosecutors’ office. While in Brazil, it was a group of prosecutors and police that began the investigation, and then the press began to cover it.

So we began in a natural manner, in the sense that as journalists we wanted to make our best contributions in a complex case that required us to join forces. And we began to function as a global newsroom, not at the scale of ICIJ but with that spirit. The goal was to go wherever we needed to go and add journalists in the countries where it was necessary to access information, and work in a collaborative manner.

You can compete fiercely in league matches and then be together on the national team. – Gustavo Gorriti

There has been a great deal of information about the Odebrecht case revealed in witness confessions and charges filed by prosecutors. How was the leak in the Bribery Division investigation different, and how does it advance our understanding of the case?

Salazar: This investigation is a very important contribution, because with the collaboration agreements which the company has signed with various attorneys general in the region, it means the company is going to have to give information they are requesting and confirm the information that they haven’t submitted. There have been omissions on the part of the company about some payments, and we as journalists have worked to corroborate that.

It is important above all to countries where prosecutors have not advanced in a decisive manner. For example, the case of the Dominican Republic is extremely emblematic. The Dominican Republic was the first country that signed the collaboration agreement between the company and its prosecutors, but publicly there has been very little disclosed about any advances. It is suspected that there is very little will on the part of prosecutors to advance the Lava Jato case.

And so in some countries, this investigation will be extremely important, not only so the company collaborates with more information, but so that prosecutors in these countries have to account for why they haven’t advanced in the investigations.

Gorriti: This adds an additional phase to the investigation. It complements what is already done in countries where there has been a lot of progress, like Peru, and helps to open the scenario in other countries where there has been less of an advance. In all countries, it is a substantive contribution.

It has another advantage, which is that it comes when Odebrecht has already reached leniency agreements for cooperation with governments and prosecutors. In all those – thanks to the fact that Odebrecht is in a very strict compliance program – the capacity to corroborate will be very quick. There won’t be a company or a group that resists giving the information, on the contrary, they will confirm. In some cases, it will be ‘Oops, I forgot!’ In others they will say they just discovered it. But without a doubt, it is an important investigation at the hemispheric level.

Normally, your networks work in parallel and sometimes even in competition in your coverage of Odebrecht. What has the experience been like of collaborating with each other on this project?

Gorriti: Both competition and collaboration are necessary and positive, for the development of investigative journalism in particular. I think they are necessary and complementary in many aspects of life. You can compete fiercely in league matches and then be together on the national team.

Salazar: The project by ICIJ is a great opportunity to join forces. From Investigate Lava Jato, we see that there is excellent work that the network led by Gustavo is doing. What counts is this: with the joining of forces to complement each other in our findings, it’s the audience that wins.

What will happen next in the Odebrecht case? What are the next developments that readers should expect?

Salazar: The pace of advances is very different in different countries, and the hope is that after this new investigation, there are positive advances. They have still not finished telling the story of what happened in countries like Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. In countries in Africa like Angola and Mozambique, everything still remains to be told.

In that sense, it is a moment for international cooperation between prosecutors, who also work in a network, to ask themselves what they can do in these cases. And there is a big question for Brazil about how it can contribute to the investigations in those countries where there aren’t the conditions to advance.

Gorriti: I think is very probable that in the next few months, if the devil doesn’t stick in his tail [barring unexpected malfeasance], we will learn much more than we what we know now. And that will take place through additional confessions. We had arrived at a certain point due to confessions, then this investigation from ICIJ greatly widens the scope of what is known, and new confessions will come from other people.

In countries like Venezuela, a lot is known but much more is still being ignored. When it is learned in Venezuela what there is to be known, the depth of the robbery will be much greater than in any other country. It is not easy to go from a powerful oil producer to a fourth-world country.

This project has served to provide an advance, an additional push to the investigation, so that it can proceed in a unified manner in Latin America. And it has also served to show, in diverse countries, the method by which this should be accomplished. Here in Peru, along the lines of what was done in Brazil, there have been great advances due to confessions. I imagine that in other countries, where there is sufficient capacity and political will, they will do something similar.

Until then, it will have to be investigative journalism revealing one thing after another.