US ‘perfect playground’ for laundering money linked to environmental crimes, new report finds

The United States’ reputation as a hub of financial secrecy has attracted criminals from around the world, including those profiting from the destruction of the Amazon.

The United States has become a destination for the proceeds of environmental crimes, undermining global moves to stem illicit financial flows and combat the climate crisis, according to a new report by a prominent anti-corruption advocacy group.

The report by the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition, published on Oct. 26, said that “critical gaps” in the U.S. anti-money laundering system are vulnerable to exploitation by criminal groups, including those behind the destruction of the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical rainforest.

According to FACT, which represents more than 100 international transparency and conservation groups, the prevalence of abuse-prone shell companies and other secretive entities — which allow bad actors to anonymously stash dirty money in the U.S. and invest in real estate — are a key part of the problem.

“Financial secrecy makes the U.S., in some ways, the perfect playground for criminals looking to stash the illicit proceeds of environmental crimes,” FACT’s report said. The country “has a crucial role to play in denying financial safe haven to criminals that would degrade the Amazon,” the report said, which “poses a major climate risk for the world as a whole.”

Deforestation, and the subsequent loss of so-called “carbon sinks,” which absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, is one of the major causes of climate change.

“Unless the U.S. implements comprehensive reforms, including the weaknesses that are described in the report, it will continue to provide an avenue for criminal actors wanting to abuse our financial system and launder environmental crimes proceeds,” said Ian Gary, the coalition’s executive director, at an event in Washington, D.C., to launch the report.

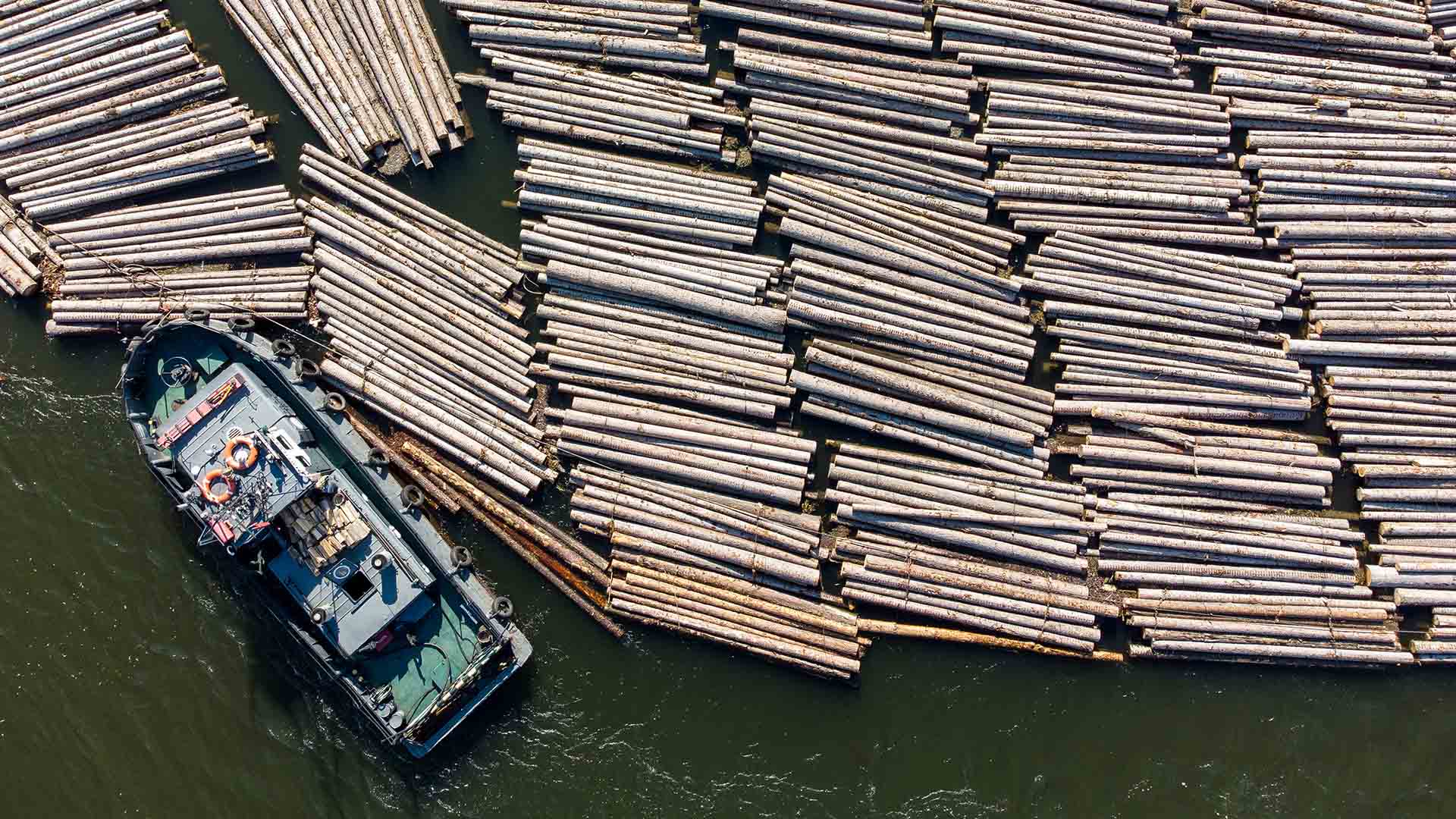

According to Interpol, illegal proceeds from environmental crimes, including illegal logging and mining, amount to $281 billion a year, and are often linked to corruption.

“Many of the people we interviewed highlighted the importance of anonymous shell companies in these environmental crimes,” Gary said. “They can be used to conceal payments to criminal organizations. They can be used as a getaway vehicle to launder the proceeds of environmental crimes. They can be used to evade civil accountability, and they can be used to facilitate [other] kinds of convergent crimes, such as corruption and tax evasion.”

The FACT report calls for the U.S. to implement its long-awaited database of company owners and to ensure foreign law enforcement is able to access the database when investigating environmental crimes. It also urges U.S. lawmakers to close loopholes that allow white-collar professionals who create and administer opaque financial structures to escape accountability.

FACT’s analysis focuses on forestry crimes and illegal mining in Peru and Colombia, and is partly based on interviews with law enforcement officials, conservationists and investigative journalists from the two South American countries and the U.S.

One case study in the report involves a Nevada company, Global Plywood and Lumber Trading LLC. In 2021, Global Plywood pleaded guilty to purchasing more than 1,000 cubic meters of wood ー 92% of the company’s imported wood ー that had been harvested illegally in the Peruvian Amazon. While under investigation by U.S. authorities, Global Plywood’s owners declared bankruptcy. The move allowed them to dissolve the company and dodge a likely court-ordered compliance plan, the report said.

Global Plywood was prosecuted by the U.S. Justice Department under the Lacey Act, which bans the trade of illegally harvested fish, wildlife, plants and plant products, such as timber and paper. But critics of the law argue it is often difficult to enforce because U.S. authorities must prove that a foreign law has been violated.

Julio Cusurichi, an indigenous leader of Peru’s Shipibo-Conibo community, said in a video clip shown at the launch event that his people have experienced the negative impacts of unregulated mining firsthand.

“The rivers are contaminated by mercury, which has poisoned the fish, which affects our daily diet. In turn, people in the community are found to have mercury in their hair and their blood,” said Cusurichi, who is president of the Federación Nativa del Río Madre de Dios y Afluentes. “It’s slowly killing our people, our fish and our rivers.”

‘Low risk, high reward’

U.S. financial authorities have recently sounded the alarm over illicit money flows linked to environmental crimes, which are considered the world’s third-largest category of crime.

In September, Andrea Gacki, the director of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, said that crimes involving natural resources are typically considered “low risk, high reward” offenses by perpetrators because enforcement is limited. But their impact on society should not be underestimated.

“These crimes not only threaten fragile ecosystems,” Gacki said, “but are often related to other illicit activities — specifically, corruption, terrorist financing, money laundering, human trafficking, or drug trafficking.”

U.S. government agencies have taken a number of actions, she said, including sanctioning wildlife traffickers, sharing information between agencies and alerting banks to illicit finance threats related to environmental crime.

But an ICIJ investigation into the certification of forest products found flaws in the U.S. sanctions intended to combat the import of timber of uncertain legal origin, such as that harvested in conflict zones.

Earlier this year, ICIJ’s Deforestation Inc. showed that timber traders in Florida, Maryland and other states continue to import teak from Myanmar — where the military regime controls the natural resources sector — despite 2021 U.S. sanctions against the state-run timber company, Myanmar Timber Enterprise.

In the past two years, U.S. companies have imported an estimated 3,000 tons of Myanmar timber, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency, a U.K.-based environmental watchdog group. U.S. importers sidestep the law by not trading directly with the blacklisted MTE but instead with non-sanctioned Myanmar exporters and middlemen based in Singapore, Thailand and other third countries.

In the aftermath of the ICIJ investigation, the Justice Department announced the creation of a new interagency task force to bolster efforts to identify, investigate and prosecute illegal trafficking in timber linked to environmental and other crimes.

U.S. lawmakers are also considering adding illegal deforestation as one of the unlawful activities listed in the anti-money laundering statute. The proposed law, dubbed the FOREST Act, would prohibit commodities originating from deforested land from entering U.S. markets. It was introduced to the Senate in 2021 but has since stalled.

“[The FOREST Act] would close very important loopholes and significantly increase transparency in supply change and accountability for traders and companies, because it would require importers to trace the commodities back to their source,” said Susanne Breitkopf, Deputy Director of the Forest Campaign.

In its report, FACT says that the U.S. should add all “nature crimes” as a predicate offense for money laundering prosecution, following the lead of Peru and other countries around the world, to increase interagency collaboration in tackling environmental crimes.

Enablers remain ‘a crucial blind spot’

FACT’s new report described the lack of due diligence requirements for intermediaries such as trust companies, lawyers, art dealers and others as a “crucial blind spot” in the U.S. anti-money laundering system. While officers working at financial institutions are required to investigate their clients and sources of funds, other white-collar professionals are not.

In 2021, ICIJ’s Pandora Papers exposed the U.S. as a major destination for foreign assets. The investigation was based on 11.9 million leaked records from 14 financial service providers that help politicians, business people and criminals hide wealth in tax havens around the world.

The investigation showed how, over the past decade, South Dakota, Nevada and more than a dozen other U.S. states have become leaders in the business of peddling financial secrecy. Using documents from the Pandora Papers, ICIJ and The Washington Post identified nearly 30 U.S.-based trusts linked to foreigners personally accused of misconduct or whose companies were accused of wrongdoing, including environmental crimes.

Among them was Federico Kong Vielman, a Guatemalan businessman whose fortune was derived from his family company, Nacional Agro Industrial SA, or Naisa. In 2016, after U.S. environmental authorities found that the company had released pollutants into Guatemala’s Pasion River, Kong Vielman moved $13.5 million into a South Dakota trust. Naisa, which was not charged, told ICIJ that it followed the law and did not pollute the river.

As a result of the Pandora Papers investigation, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced legislation that would require lawyers and other professionals to investigate foreign clients seeking to move money and assets into the American financial system.

The proposed law, known as the Enablers Act and hailed by anti-corruption advocates as critical to curbing financial crime in the U.S., was later blocked by the Senate.

Meanwhile, another lauded reform, the beneficial ownership registry, has also been beset by delays and mounting disagreements over who should be able to access it.

“Unless the U.S. implements comprehensive reforms,“ FACT’s report said, “it will continue to provide an avenue for criminal actors wanting to abuse our financial systems and launder environmental crime proceeds.”