Zimbabwe published a list of more than 1,800 individuals and companies last week that the government said illegally transferred money abroad, including several who appear in the Panama Papers.

The list was the result of a three-month amnesty that allowed companies and individuals to return money to the country without prosecution. The list named those who had not done so.

In announcing the results, President Emmerson Mnangagwa said that $826 million – more than half of an estimated $1.42 billion stashed outside Zimbabwe – was not returned during the 90-day amnesty period.

“The authorities have no other recourse to cause these entities and individuals to respond, other than to publicize the names of the entities and individuals so that the concerned parties take heed of the importance of good corporate governance,” Mnangagwa said in a statement.

Those on the list who can prove they have declared the assets may still approach the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe to have their names removed, the statement added. The government-owned bank is responsible for monitoring Zimbabwe’s foreign financial flows.

Five mining companies were the biggest culprits, according to the list, with two firms, African Associated Mines and Marange Resources, accused of not returning $62 million and $54 million, respectively.

Others holding assets abroad included cargo, cotton, tobacco and refrigeration companies and the Archdiocese of Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital, which allegedly failed to account for more than $10,000. Chinese business owners were strongly represented.

One former finance minister criticized the decision to publish names as “defamatory” and called it a “Mickey Mouse list.” The BBC reported that a representative from China’s embassy in Zimbabwe rejected the list as lacking credibility.

At least three companies and business owners in Zimbabwe named on the list also showed up in the Panama Papers, ICIJ has found. But their offshore assets have not been previously reported in detail.

Harare-born businessman Derek Kitchen, who founded a food and beverage supply company in the 1970s, moved more than half a million dollars out of Zimbabwe “in cash or under spurious transactions,” according to the government.

Kitchen owned SK Cheminvest Ltd., a company registered in the British Virgin Islands in 2010, according to the Panama Papers.

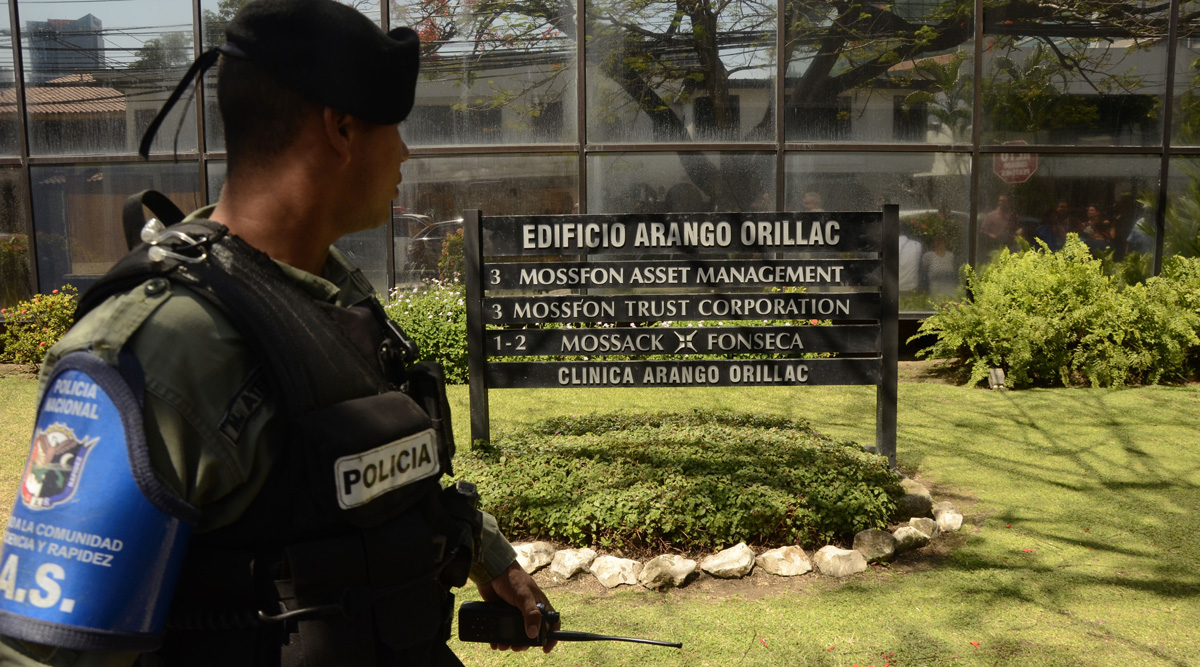

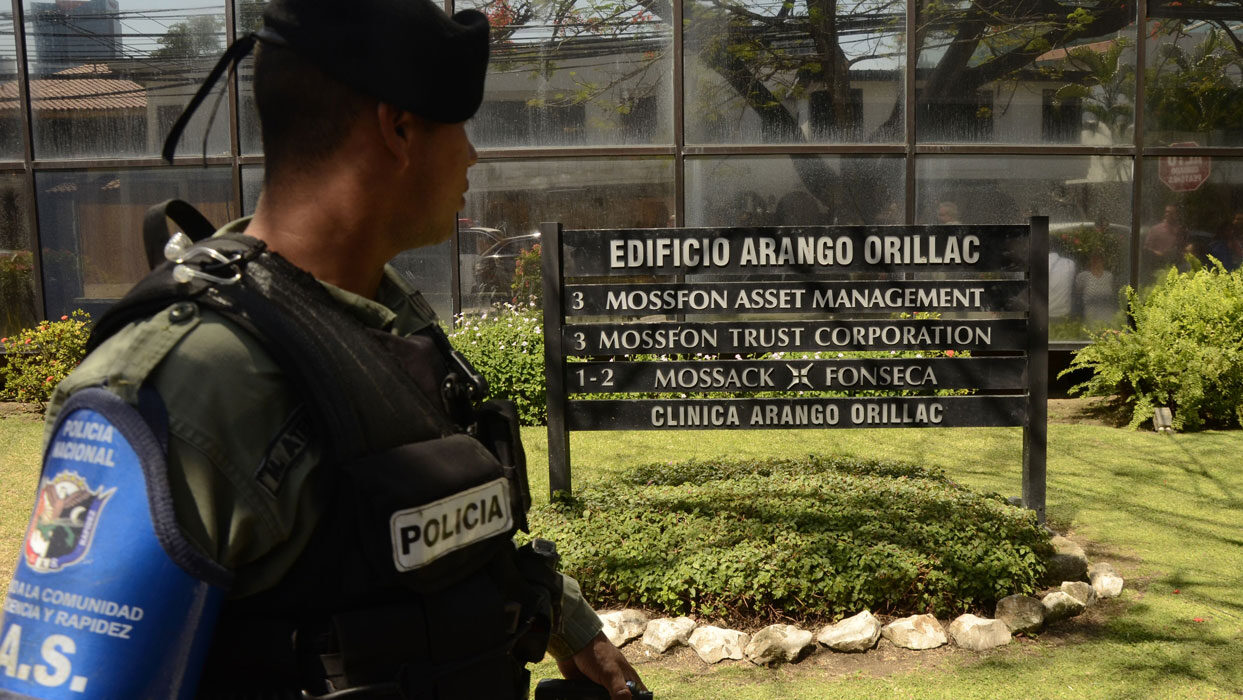

The company provided “consultancy services” to farmers in Zimbabwe and South Africa, according to emails sent between a Mauritius-based management company and Mossack Fonseca, the offshore law firm that helped set up SK Cheminvest Ltd. and whose files formed the basis of the Panama Papers investigation.

Kitchen, who lives in Cape Town, owned SK Cheminvest through stand-in or “nominee” shareholders and through the Sunhouse Trust.

“There are few legitimate reasons for a Zimbabwean businessperson to use an offshore company or trust registered in a secrecy jurisdiction like the BVI other than to conceal personal identity,” said John Christensen, director of the nonprofit Tax Justice Network.

Although not specifically addressing SK Cheminvest, Christensen noted that “the anonymity provided by a secret offshore company or trust makes it easy for people who engage in tax evasion, bribery, fraud, evading creditors, embezzlement and similar crimes to thwart police and other investigators from trying to ‘follow the money’.”

Kitchen told ICIJ that “the whole thing is a screw-up by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe.”

Kitchen said he received approval to remove the funds in relation to a property sale and added that he would be writing to the Reserve Bank to complain about his appearance on the list.

Kitchen said that SK Cheminvest no longer exists and that his trust fund managers had “cancelled” the business.

The Zimbabwe government’s list of companies with offshore assets includes Progene Seeds, a business that produces corn and bean seeds and provides cattle semen to Zimbabwean farmers. The company sent more than $10,000 overseas for goods that never arrived in the country, according to the list.

Progene Seeds Ltd., owned by geneticist Andrew Henderson, was created in the British Virgin Islands in 2003, according to the Panama Papers. The company sold plant genetic material in Zimbabwe and other countries in southern Africa and received royalty income from germplasm sales by other agricultural companies, Progene Seeds’ 2015 business plan noted. Progene Seeds also provided consulting services.

Without commenting on Progrene Seeds specifically, Tax Justice Network’s Christensen said “unspecified ‘consulting services’ are an old favorite when it comes to hiding bribe or kickback payments.”

“It is hard for investigators to establish what those services consist of, and what the real value of such services (if any services were indeed provided) might be,” Christensen said. “This explains why ‘consulting services’ are frequently used as a mechanism for shifting money illicitly to offshore destinations.”

Henderson did not respond to written questions and hung up on an ICIJ reporter.

Zimbabwean President Mnangagwa promised to tackle corruption after he replaced Robert Mugabe, who led the country for 37 years.

On social media, however, Zimbabweans noted how few individuals or companies on the list were linked to politicians long-suspected of graft and bribery.

European countries and the United States have sanctioned Zimbabwean politicians and companies controlled by the Mugabe government since the early 2000s for undermining democracy. European asset freezes and travel restrictions continue against former president Mugabe and his wife, Grace.

After the initial Panama Papers disclosures in April 2016, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe announced investigations into more than 250 individuals and companies named as having done business with or through the law firm Mossack Fonseca.

Zimbabwe has not commented on the probes since the announcement.