RUSSIA GAMBIT

Uber forged deals with top Putin allies in failed bid to break into Russian market

To “tame the bear,” Uber partnered with a Kremlin bank and offered stock enticements to Russian oligarchs, internal memos reveal.

On a rainy spring evening in 2016, Russian tech tycoons and politicians sat down for a three-course dinner at the Moscow City Golf Club, an exclusive meeting place near the Moskva River. The man of the hour was Travis Kalanick. Hoping to expand Uber’s business in Russia, the company’s chief executive chatted up dinner guests about big data, artificial intelligence and other things tech.

“God love the Russians, where business and politics are so….cosy,” Uber’s European public policy chief Mark MacGann emailed two company executives ahead of the dinner.

As Uber battled local governments and eluded or challenged regulations in Western democracies, some executives went to extraordinary lengths to grow the company’s business in Russia, at the time one of the world’s most attractive but oppressive marketplaces.

The Uber Files, a cache of internal Uber documents obtained by The Guardian and shared with ICIJ and 42 media partners, show some executives identified politically connected Russian billionaires and courted their favor through appeals from former U.S. and U.K. government officials, and lucrative deals involving company stock. Those oligarchs are now under Western sanctions.

Uber’s efforts to win favor and a long future in Russia were ultimately unsuccessful.

In response to written questions, Uber told ICIJ and its media partners that no one at the company today cultivated relationships with oligarchs.

“Our current leadership disavows any previous relationships with anyone connected to the Putin regime,” Uber spokeswoman Jill Hazelbaker said. “Current Uber management thinks [Russian President Vladimir] Putin is reprehensible and disavows any previous association with him or those close to him.”

The leaked documents, containing more than 124,000 emails, text messages, PowerPoint slides, invoices of spending, strategy memos and other types of records, provide insight into the risks and rewards of breaking into authoritarian markets and operating in them.

In China, Uber invested heavily and met with multiple state-owned enterprises and local government officials but eventually lost out to a local rival. In Saudi Arabia, Uber turned to its policy chief — former Barack Obama adviser David Plouffe — to push for favorable ride-hailing regulations. The company offered Princess Reema bint Bandar Al Saud a spot on Uber’s advisory board.

In Russia, the documents reveal, Uber insiders raised concerns that a proposed deal with a Russian consultant might run afoul of U.S. anti-bribery laws.

A nine-page internal briefing document lays out challenges the San Francisco-based giant faced in Russia and tactics to overcome them. Uber said it needed “to keep a low profile, given the current geopolitical climate.” One of its “key objectives” was to “become an active player for the law making process” by identifying “key business and political stakeholders.”

The document lists key Uber figures, including Plouffe, along with a slew of oligarchs and politically connected billionaires it calls “allies,” such as Sberbank’s powerful chief executive, Herman Gref, and Mikhail Fridman, co-founder of Alfa Group, a multinational Russian conglomerate. The document describes how the company could use those allies “to protect the business from attacks by competitors and ‘invisible forces.’”

“I think we want someone aligned with Putin,” Emil Michael, Uber’s chief business officer, said in an email exchange with colleagues in 2014 about potential Russian investors.

A spokesman for Michael said he “doesn’t recall any specific references to Uber wanting an investor aligned with Putin.” The company vetted all investors, he said.

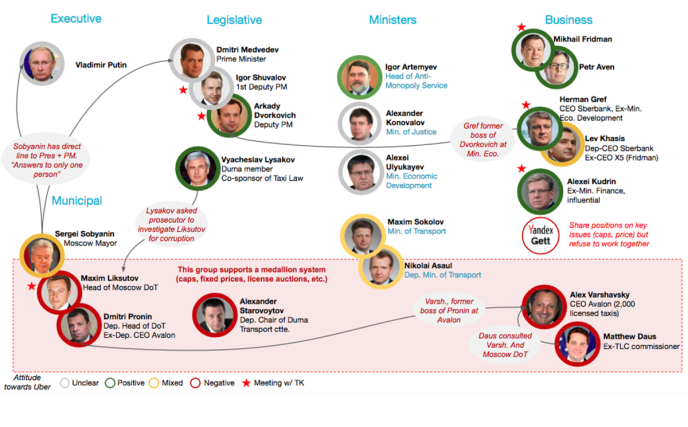

Uber mapped the relationships among billionaires and political figures, including Putin, in a briefing book prepared for Kalanick ahead of the Moscow dinner:

Taming the bear

As it sought to “tame the bear,” as one internal memo put it, Uber forged deals with several Putin allies, including Gref’s Sberbank; LetterOne Holdings investment firm, owned by Putin-loyalists Fridman and Petr Aven; and USM, a holding company co-owned by Russia’s sixth-richest person, Alisher Usmanov.

After signing a deal with Sberbank in September 2015, Gref introduced Uber to the mayor of Moscow, and the bank promoted Uber on its mobile banking platform and launched a vehicle financing program for Uber drivers, emails show. Sberbank customers also received loyalty points on their Uber trips, bringing in about 20,000 new riders in 2015 alone. In addition, Uber explored making the bank’s credit card the payment card of choice for Uber rides in Russia and offering a program to Sberbank that would make it easier to reimburse employees for using Uber, the documents show.

Is it a normal practice for the largest state bank of the Russian Federation to advertise services, potentially dangerous for citizens?

– Russian taxi drivers union

The Uber-Sberbank alliance enraged Russian taxi drivers. A taxi union wrote a letter to then-Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, saying the partnership weakened competition, drove down worker wages by undercutting prices and violated taxi laws. They even accused Uber of tax evasion and bribery.

“Is it a normal practice for the largest state bank of the Russian Federation to advertise services, potentially dangerous for citizens?” the drivers asked in the letter. “Why does Sberbank offer the most expensive and complicated lease and loan deals to others and special favourable conditions to Uber?”

Emails show the Uber-Sberbank relationship was kickstarted, in part, by Plouffe, who met with Gref during a summer trip to Russia in 2015. Throughout the life of the relationship, Sberbank was under sanctions by the U.S. and EU governments, first prompted by Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Plouffe did not respond to questions about his role in Uber’s pursuit of influential Russian investors. Gref did not respond to questions.

Hazelbaker said Uber would not engage in any relationship with Sberbank or Gref today. She added the investment would not have violated U.S. sanctions at the time.

Emails also show that discussions about a deal with LetterOne developed in late 2015. Then in late January 2016, Travis Kalanick met at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland with Alexey Reznikovich, the managing partner of LetterOne Technology, a unit of LetterOne Holdings. “Strong meeting,” a meeting summary states. “Looks like we are close to a deal.”

Devon Spurgeon, a spokeswoman for Kalanick, said Kalanick’s efforts to expand Uber’s business into Russia were limited to a trip to Russia and a few meetings. He “was asked for his involvement following Uber’s robust legal, policy, business development teams having vetted and approved the strategy and operations plans,” she said.

Spurgeon added: “Mr. Kalanick is not aware of anyone acting on Uber’s behalf in Russia who engaged in any conduct that would have violated either Russian or U.S. law.”

Kalanick resigned in 2017 after a series of company scandals but stayed on the board of directors until the end of 2019.

Company executives’ efforts to win favor with LetterOne led to a February 2016 announcement that the oligarch-owned investment firm had bought a $200 million stake in Uber as part of a “strategic partnership.”

Part of that deal was kept private: Uber had offered the investment firm $50 million in stock warrants, representing the right to purchase Uber stock at a set price. According to an email from Uber’s public policy executive MacGann, the offer was made to encourage the firm to help Uber politically in Russia and to underwrite “the day-to-day heavy lifting that they would undertake on our behalf in the Duma and with the presidential administration.”

Documents show that LetterOne executives were helpful in connecting Uber with other influential Russians. For example, they connected Uber with Alfa Bank’s deputy chairman, Vladimir Senin, who, according to an Uber memo, managed to slip key pro-Uber provisions into a federal taxi bill. The bill didn’t become law, however.

According to the Uber Files, Uber signed a deal with Senin, now a member of the Duma, to help Uber on both the legislative and regulatory fronts. Uber consultant, Benjamin Wegg-Prosser, is quoted in one document saying Senin “had been paid properly for his support.” In response to questions, Hazelbaker confirmed that Uber paid at least $300,000 for Senin’s “government relations work.”

Uber’s then head of business in Europe, the Middle East and Africa Fraser Robinson told colleagues that Uber’s lawyers were concerned that hiring Senin on top of providing LetterOne with stock warrants could breach the U.S. law against bribing foreign officials. The lawyers warned that payments could be seen as bribes to “grease the skids,” Robinson said.

Robinson did not comment on any potential U.S. anti-corruption violations. Hazelbaker said Uber would not do business with Senin today.

In response to ICIJ’s questions, MacGann said he did not support payments to Senin. “I had concerns about LetterOne’s insistence that we pay large sums of money to one of Alfa Bank’s top executives,” he said.

LetterOne, in a written statement, said that neither the firm nor its co-founders ever lobbied for Uber and that Senin’s role was “entirely at the discretion of and the responsibility of Uber.”

Aven said he had nothing to do with any Uber stock warrant deal or lobbying. “I stay absolutely out of politics,” he said in a telephone call with ICIJ’s partner The Guardian.

Fridman, also in a phone call with The Guardian, said he “was not involved with the Uber investment or with any lobbying.”

Uber denied paying stock warrants in exchange for a lobbyist delivering favorable rules or laws. “The warrants vested based on Uber’s relative growth in Russia, as measured by the number of trips happening in the country,” Hazelbaker said.

The “Taming the Bear” memo noted that Uber had the “personal support” of Fridman, Aven and Gref. “With their support we have, in theory, a direct line into the Kremlin,” the memo said. “The personal involvement of Mikhail Fridman and Pyotr Aven (L1) and Herman Gref (Sberbank), all of whom are very close to Vladimir Putin, means that (in principle) we have access to top-level political guidance and support.”

An email from Uber’s MacGann says that LetterOne principals also agreed to help in Belarus, a former Soviet satellite that remains under heavy Kremlin influence. As authorities in Belarus’ capital were revoking Uber drivers’ licenses and demanding driver tax data, LetterOne co-owner Aven planned to step in and “push these points to the Deputy Prime Minister in Minsk,” the email from MacGann said.

In a phone call with The Guardian, Aven denied intervening in Belarus.

The LetterOne relationship was arranged partly by Lord Peter Mandelson, a former U.K. government minister, and Wegg-Prosser, former communications director to Prime Minister Tony Blair, the Uber Files show. Their strategic advisory firm, Global Counsel, provided intel on Russian influencers with “close links and loyalty to Kremlin.” Wegg-Prosser was in direct contact with LetterOne’s Petr Aven, asking if he could set up a meeting between Uber and Putin’s chief of staff. In 2016, Global Counsel had an $87,000-a-month contract with Uber, leaked emails show. During the first few months of that year, a fourth of its compensation would pay for its work on Russia.

In response to questions from ICIJ partner The Guardian, a spokesman for Global Counsel said Uber appointed the firm to “provide advice regarding the company’s international strategy,” and that all Global Counsel’s advice followed relevant European Union and U.K. guidelines.

The Uber Files also show Uber offered stock warrants to USM, the holding company co-owned by the Uzbek-born oligarch Usmanov. The value of those warrants was $2 million, a USM spokesman said.

He said there were no political overtones to the deal and that it’s “absurd to suggest that the holding or its shareholders could act as ‘political lobbyists’ for Uber.”

“Mr Usmanov never met with any of Uber’s representatives,” he said.

Despite its efforts, Uber’s Russia venture didn’t work out.

In 2017, Uber agreed to merge its Russia business with the Russian internet company Yandex, which operates a ride-hailing service, into a $3.7 billion joint venture controlled by Yandex. Since then, Uber has sold more of its stake.

After this year’s Ukraine invasion, Uber announced plans to cut its financial ties with Russia entirely.

Contributors: Jelena Cosic, Harry Davies, Ian Duncan