The European Commission has added Panama, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia to an expanded blacklist of 23 countries it believes are failing to address a high risk of money laundering or terrorist financing.

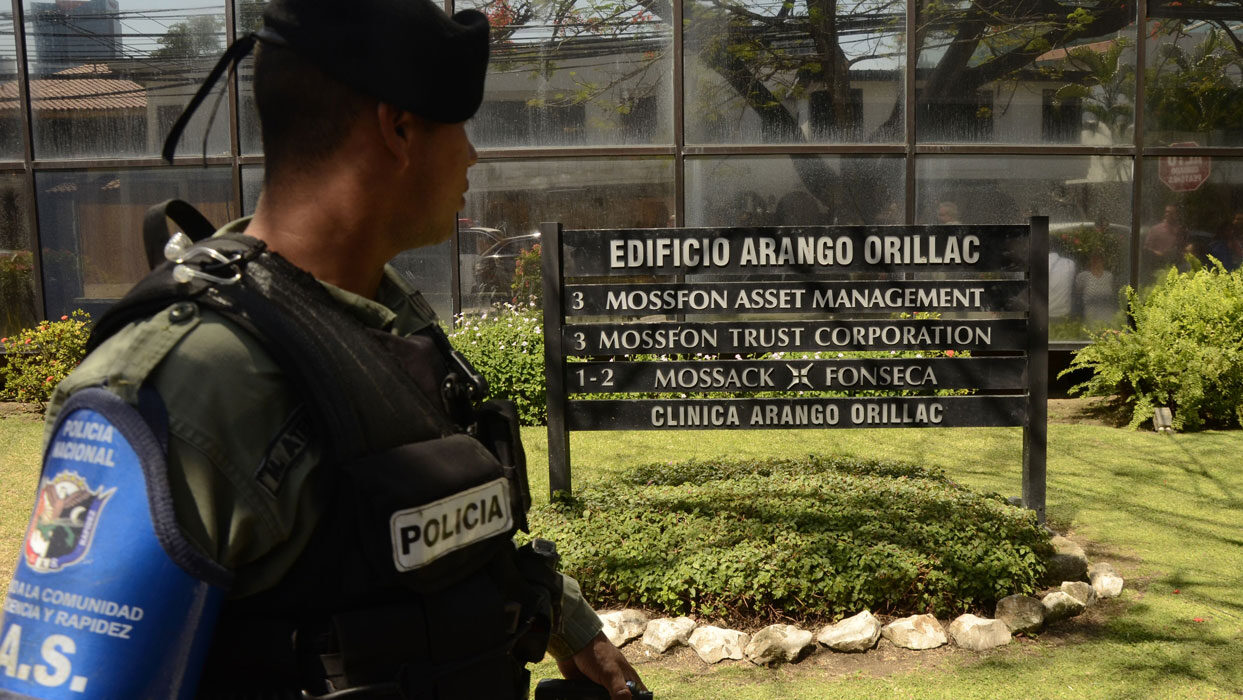

The ‘dirty money’ list, published on Wednesday, updates an earlier 15-strong EU list and is the first time assessors have used new, tougher criteria, in part introduced in response to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ Panama Papers investigation.

The list is expected to provoke lobbying by affected nations. Saudi Arabia and Panama have protested already over their inclusion, while the United States is furious at the listing of four of its overseas territories. Other critics have noted that the list omits many notorious tax havens, secrecy jurisdictions and laundering hotspots.

The fresh criteria are part of a wider strengthening of EU anti-money laundering rules that Commission vice president Frans Timmermans said were partly a response to “the vast financial dealings uncovered by the Panama Papers.” They took two years to develop and were finally adopted in April last year.

Yet to be signed off by other EU institutions, the list could be in force as early as May. Banks and and other financial institutions will then have to carry out additional checks when processing payments for customers from blacklisted countries.

Dirty money is the lifeblood of organized crime and terrorism. I invite the countries listed to remedy their deficiencies swiftly – Věra Jourová

“We have to make sure that dirty money from other countries does not find its way to our financial system,” said Věra Jourová, the EU’s Commissioner for Justice. “Dirty money is the lifeblood of organized crime and terrorism. I invite the countries listed to remedy their deficiencies swiftly.”

Included on the blacklist are four U.S. overseas territories – Guam, American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico – prompting protest from America.

In a statement, the U.S. Treasury Department attacked the credibility of the list, describing it as “flawed” and “not … sufficiently in-depth.” It pointed out that another widely-recognized intergovernmental organization, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), already carried out detailed work in this area, producing its own blacklist.

“The Treasury Department does not expect U.S financial institutions to take the European Commission’s list into account,” officials said in a statement criticizing the commission’s methodology.

According to the Financial Times, at a meeting of EU ambassadors last week France, Germany and the United Kingdom expressed reservations about the Commission naming countries not already on the FATF’s blacklist. If this reported opposition hardens, the Commission could be forced to hastily revise the lineup.

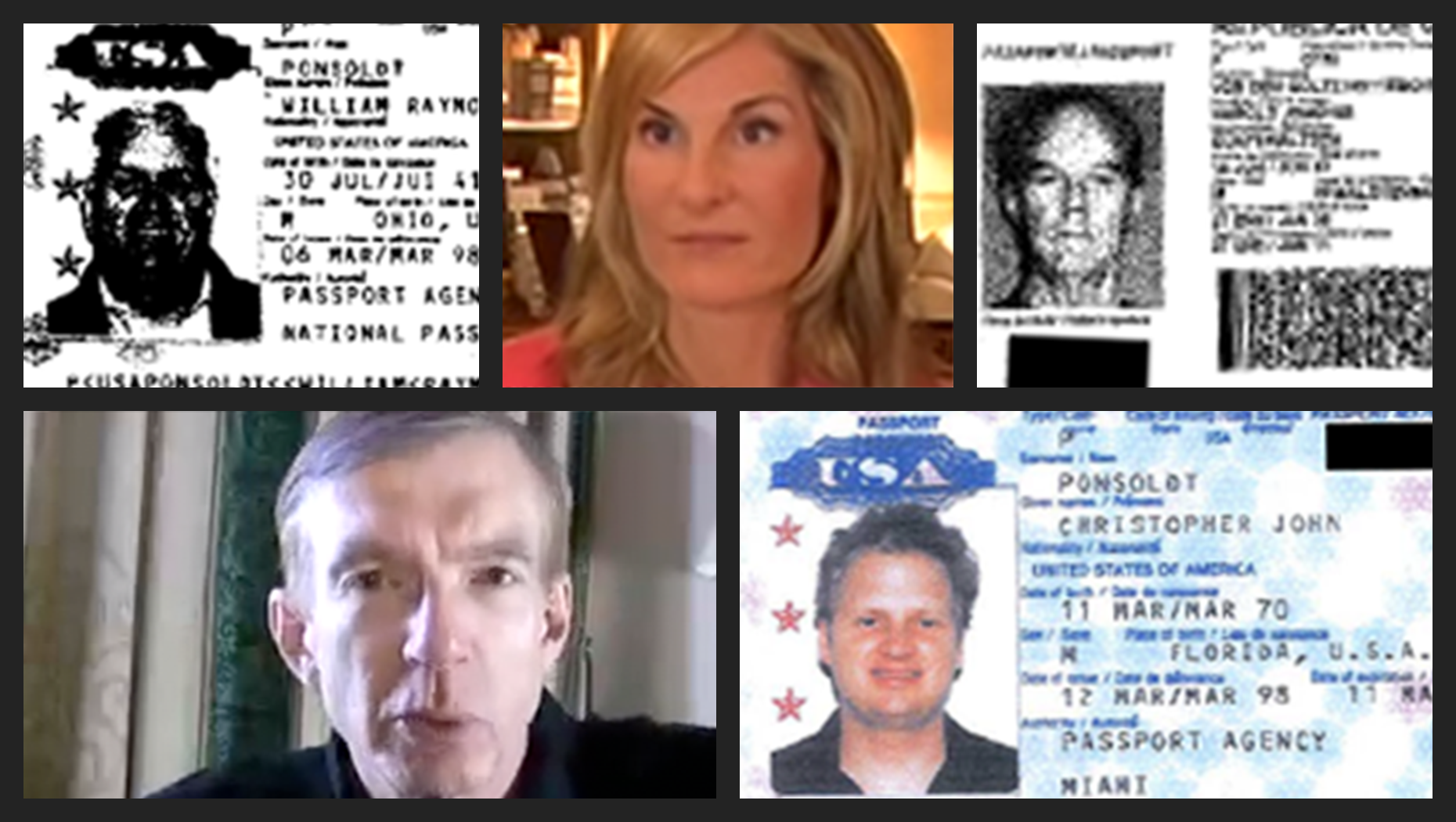

Many of the U.K.’s overseas territories and crown dependencies – several of them well-known tax and secrecy havens – had initially been under consideration as contenders for the Commission’s list but were eventually omitted. This includes the British Virgin Islands, the jurisdiction most used by customers of Mossack Fonseca, the law firm at center of the Panama Papers scandal.

Also considered but ultimately not included was Switzerland, one of the world’s leading bank secrecy jurisdictions.

Laure Brillaud, policy officer on anti-money laundering at Transparency International EU, said: “It is good news that the Commission is creating its own blacklist of countries based on effectiveness criteria – including the level of financial secrecy – leading to some welcome additions to the existing FATF list such as Panama, Saudi Arabia and U.S. offshore centres.”

But, she added, there were notable omissions. “Let’s just think of this long list of jurisdictions where offshore companies can be set up with the click of a mouse or that are thriving on financial secrecy such as Mauritius, BVI, Cayman Islands, UAE, St. Kitts and Nevis, Singapore, Hong Kong, etc.”

The criteria used by Commission also mean no EU member state can make the list, despite the recent money laundering scandal at the Estonian branch of Denmark’s Danske Bank.

Six African countries are on the list – Libya, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Botswana, Ghana and Nigeria – though there is no mention of the mineral-rich nations of the African Great Lakes region, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, which have been ravaged by war, looting and terror.

Five Middle Eastern countries make the list – Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Saudi Arabia. The United Arab Emirates and Israel are not included. Last December, Israel became the 37th member of the FATF, and the first member to have once been on the same organization’s blacklist. UAE has also recently adopted many FATF recommendations.

Further east, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and North Korea are the only countries to feature, while Malaysia escapes mention, despite the 1MDB financial scandal.

Aside from Panama, the remaining countries on the Commission’s blacklist are all small island territories, most of them in the Caribbean Sea or South Pacific. They are Puerto Rico, Samoa, American Samoa, Guam, Trinidad and Tobago, the U.S. Virgin Islands and the Bahamas.

Panama’s ambassador to the EU, Miguel Verzbolovskis, said his country’s inclusion on the Commission’s list amounted to “unfair punishment.”

The Commission’s blacklist is focused on risks relating to money laundering and terrorist financing and is separate from the EU’s tax haven blacklist, which was drawn up without the Commission’s involvement. The latter list – in part a response to ICIJ’s Panama Papers and Paradise Papers investigations – has been criticized, not least by the EU’s finance commissioner Pierre Moscovici who said it had been weakened by “diplomatic compromises.”