A veteran French politician of the centre left, Pierre Moscovici served as the country’s finance minister before moving in 2014 to the European Commission, where he holds the role of commissioner for finance, the economy, tax and customs. His powers in relation to tax, however, are limited. In fact, policies on tax – aside from Europe’s sales tax, VAT – are decided independently by each of the EU’s 28 member states. But, in response to years of tax scandals exposed by the media, many countries have called for coordinated, pan-European efforts to close loopholes and present a unified front against tax avoidance and evasion.

Meanwhile, a small number of member states resisted change. Why? These are EU countries that have thrived by marketing loopholes in their own tax codes that appeal tax avoiders and evaders. Closing loopholes would be bad for their economies. So far, these countries have sought to block or delay European tax reform. Moscovici’s five-year term as commissioner, which ends next year, has been marked by a string of tax scandals that have reflected badly on several member states. Much of his time has been spent exploring how to coordinate a European response. Not everyone is delighted with the progress he has made. Including himself.

Q: Did the Paradise Papers have any impact on the EU’s efforts to produce a tax haven blacklist?

A: Well, first – and I say this all the time – I’m very thankful for what you’ve done. Not only with the Paradise Papers but in all the recent years. Those scandals were always very bad news for the citizens who see that some people are always ready to do anything for a bit more money, even when they have lots. It’s also good news for the policy makers. And, frankly speaking, without you, I think we would have had – I wouldn’t say nothing – but very little of what we achieved during the recent years. I’m afraid there wouldn’t be any kind of list at all, that the member states would have managed to water down or reduce etc. So, you’ve got a very important role there.

Q: You were quite honest both in terms of what you felt the blacklist achieves and what it does not. Are EU efforts to tackle tax havens hampered by the constant need to reach unanimous decisions among member states?

A: Well, my judgment is the following: This list is not the Commission’s list. The criteria were chosen by member states, on our proposals. But they didn’t take all of the criteria we proposed – and the process was inter-governmental. And they chose [their own committee, which is not part of the European Commission] knowing that it would lead to something, I would say, that would be more moderate than it could have been.

Then, when I look objectively there are good elements in the list. The first one is that it exists. After all, it is the first ever EU list of tax havens. Second, its screening process, as far as I know – and I know a bit – has been serious, not complacent. Real questions were asked of all the 92 countries screened. Real commitments were required – and they were given by those countries. Third, to me what is important is more the graylist rather than the blacklist. These are the countries that are committed to change, and it maintains the process. Either they respect the commitment and they’re out of the list, or they don’t and they move into the blacklist. These are the good points. What are the weak points? Obviously there is some shyness in the list. There were some – I wouldn’t say diplomatic compromises, but certainly some countries’ commitments were taken at face value by the Code of Conduct Group and the member states, so it will be important that they [the member states together] are vigilant in monitoring their implementation. Also, there are no EU countries on the blacklist, and I think if you look at the criteria themselves you see there are harmful practices inside the EU, which also have to be considered. And, finally there are no sanctions.

Q: What is the prospect of sanctions in the future?

A: I will continue to insist on the importance of the EU and its Member States having dissuasive sanctions in place, as one of the elements to exert pressure on jurisdictions to improve their tax governance and ensure they do not create new harmful regimes. We need to have more pressure from the outside world. We cannot rely only on spontaneous leaks.

Q: The ICIJ works with what you call ‘spontaneous leaks’, but outside the EU there are very effective investigative committees, with real powers, such as the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. They are able to demand detailed information and appoint experts to probe into complicated matters of tax evasion and avoidance. Should Europe have such a body?

A: It could. It could also be the Commission doing that work with those experts. But that was not the choice made.

Q: When the tax haven blacklist was drawn up, do those member states with strong links to tax havens – such as the U.K., because of its ties to British overseas territories and crown dependencies – recuse themselves from the process? Or do they retain power of veto over whether those jurisdictions appear on the list?

A: They have a veto power. And they could have vetoed. But the point is that, objectively, those territories were not missed in the screening process. They are in the graylist – Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man, etc. – and they have made some commitments. I myself have met several times with the leaders of Jersey and Guernsey. You cannot say that they have totally changed their business model. You cannot say either that they are not changing anything. So there was no veto from the U.K.

And again, you’ve got to consider the result achieved as the first step, as a process, and the graylist and blacklist as a package. Of course, [EU decision-making that requires member state] unanimity is a problem. Of course, it would be better to have something that was totally objective. But, on the other hand, it’s not that bad if the member states are involved, because they take the responsibility. Though for that [to happen] they need to be under the pressure from the outside world. And the outside world is you – the media, NGOs, parliaments, European parliaments, etc. They are sensitive to that. So, they could not scandalously water down the list. I think there the Paradise Papers played a huge role, because without the Paradise Papers probably it would have been much more difficult to achieve the list. It would have been delayed or the temptation to water down would have been present.

Q: But some of the countries that appear on the blacklist appear to be jurisdictions that may be administratively challenged rather than aggressive in terms of their non-cooperation and business dealings with the EU.

A: Yes, so what?

Q: So is this list looking like it is refining into a list of non-cooperating, problematic jurisdictions? Or is it refining into a list of jurisdictions that administratively are so challenged that they don’t answer detailed questionnaires from European authorities?

A: I think in the blacklist you have both. Obviously, those countries that couldn’t answer are blacklisted. Some countries answered too late, which was the case with Tunisia, and they are also blacklisted. Some countries answered late but they did it a bit more efficiently so they are on the graylist. If you take the 17 [jurisdictions on the blacklist] – you’ve got authentic tax havens and countries that are incapable or unwilling to answer. If you take the 64 [on the black and graylist], then that includes all the non-cooperative jurisdictions in the view of the member states.

Q: Can we move on now to tax avoidance among multinational corporations and the European Commission’s ambition to tackle abuses by better coordinating member states’ tax processes – an proposal called the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base, or CCCTB. Has that lost momentum?

A: All in all, we still have some momentum for transparency and for convergence. But it is going to be complicated because these proposals are more structural in nature, so more difficult to negotiate. I think there is a window of opportunity, but the window is quite narrow. But I will do my best.

Q: So the chances of CCCTB working are diminishing?

A: No I think the opportunity is there, but there is still some very significant reluctance on other matters which are not linked to transparency. Which are linked to [member states’ tax] revenue loss. That’s the case for Ireland. [For decades, multinationals used Ireland as a European base, bringing investments, jobs and tax income to the local economy. But they were drawn to the country by the prospect of international tax loopholes. Moves to close these loopholes would likely prompt many to leave. – ICIJ’s editor.]

Q: What are your concerns about the Trump administration’s recent overhaul of U.S. tax law?

A: We have expressed some concern. Every country is free to act on its own tax rates, the problem is that sometimes the nominal tax rates are one thing, the effective tax rates are another one. But my real concerns are twofold: the first is that these reforms could create macro-economic imbalances by increasing the U.S. deficit and debt, which would have an impact on the world economy. Second, we feel and fear that some of the elements of the reform might damage [an agreed package of international measures to tackle tax avoidance by multinationals, known as] the BEPS initiative and also the WTO (World Trade Organization) agreements [international free trade rules] , so we have to ask them for some explanations as part of our ongoing exchanges with the U.S, bilaterally and through multilateral fora.

Q: The Paradise Papers showed that many U.S. multinationals have built tax avoidance structures by separating the rights to income from intellectual property from the location where that valuable IP is created. Do you think the latest U.S. reforms are likely to mean intellectual property rights will soon be owned where the intellectual property is created?

A: We are not yet there.

Q: As well as some international cooperation on tax reforms through the G20 and OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), there have also been tensions emerging. For example, many in the U.S. have been angered by a wave of cases brought by the European Commission ruling that EU member states have been awarding illegal sweetheart tax deals to multinationals, many of them American companies. Meanwhile, there is concern in Europe, and elsewhere, about the current U.S. administration and its ambition to use tax policy to reward international companies that create American jobs and punish those that create jobs elsewhere. Is that a difficult environment in which to build global consensus on how to make international tax systems work at their best?

A: No. Your question has an obvious answer. I would say that with the Obama administration things went quite smoothly, and they were involved a lot in the international framework, especially in the G20 and OECD. With the Trump administration, of course, that’s not the case. The U.S. tax reform has been designed for U.S. purposes and not for global purposes. When it comes to international tax matters, this administration has been less active, but they didn’t do anything that was harmful to the process either. Now with these tax reforms, well, they enter into a new period.

The U.S. tax reform has been designed for U.S. purposes and not for global purposes.

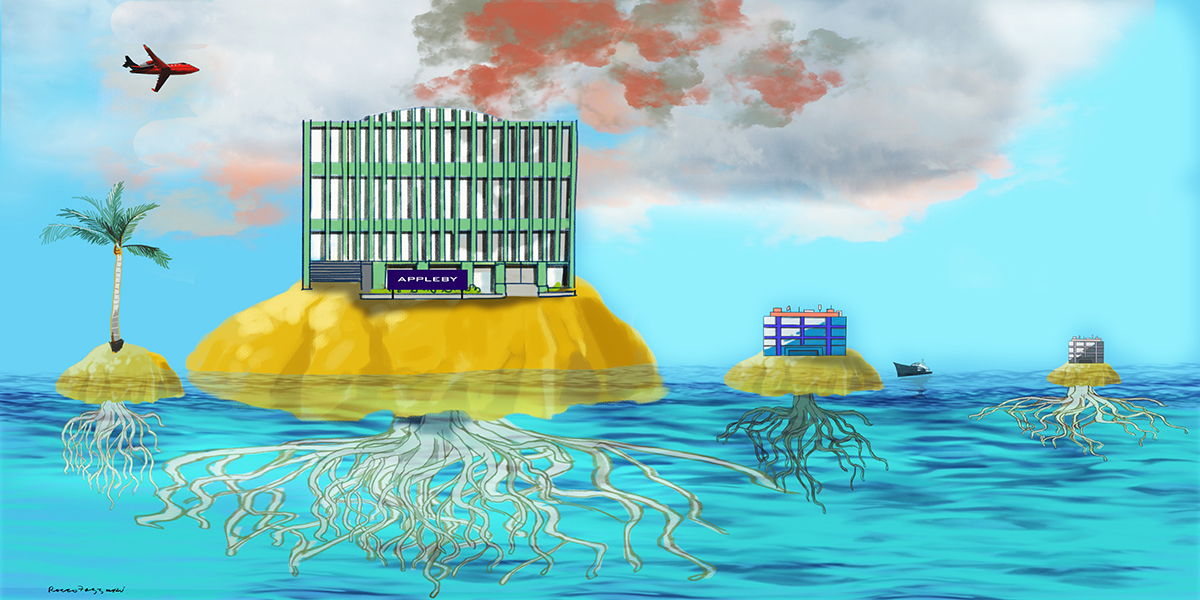

Q: Two questions relating to the UK: firstly, you may have seen in media reports, some of ICIJ’s media partners are having legal claims brought against them by the law firm Appleby. It’s a detailed matter, but do you have any opinion about that kind of action?

A: No, I cannot interfere into legal action of any kind. This is for the courts. What I can say is that the ICIJ did a tremendous job, which was in the public interest. That was a great help, it gave impetus to the fight against tax havens, tax fraud, tax evasion and aggressive tax planning – so we need you.

Q: Also on the UK, is there a risk that after Brexit, an independent UK will want to compete more aggressively on tax?

A: For the time being the UK is a member of the EU. The UK is quite cooperative in the framework of the international community. I’m a social democrat, but I worked well with George Osborne and Phil Hammond [Britain’s former and current finance ministers] on that matter. And the UK after Brexit will stay a member of G7 and G20 and so on. But of course they will defend more and more their own interest and they will be on their own defining their tax strategy. I imagine that they want very much to be competitive. But the problem is not so much about competitive tax rates, which the UK can set even today as an EU Member State. The problem is having effective tax rates that are ridiculous.

Q: In recent years, Ireland has been introducing tax reforms in response to developments internationally designed to combat aggressive tax planning, They’ve taken steps to phase out a lot of well-publicized planning opportunities. But it does seem that a number of multinationals have found other ways to use Ireland to keep their effective rates very low. Meanwhile, at the same time, Ireland seems to be emerging as a winner in terms of tax receipts and inward investments. If Ireland is emerging as a ‘winner’, does that mean international efforts to crack down on artificial profit shifting and tax avoidance are failing at the moment?

A: I’m not going to comment on that because that would be subjective. But I can answer another way: it’s not because the blacklist and even the graylist doesn’t have on it any EU member states that it means there are no problems inside the EU. There are problems inside the EU – there are heavy problems inside the EU. We know who are the usual suspects and we need to act against these problems. That is absolutely obvious.

There has been some progress – in Ireland, in Luxembourg, in the Netherlands – they are committing to BEPS or automatic exchange of information. But obviously there are some practices, or some legislation, that helps aggressive tax planning – and we will need to address that. That’s what [EU commissioner for competition] Margrethe Vestager does, and I want to do that also. And I think that CCCTB is the structural answer if we want to build the corporation taxation of the 21st century.