En Ju, Valérie, David and Fernanda.

These were the people whose stories we wanted you to hear.

Two women and two men from four countries, out of the more than 3,500 who responded to our global medical devices callout.

Four very different people whose stories represent a complex pattern of laceration and loss stretching from continent to continent.

Four voices that echo the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’s Implant Files investigation, bringing to life the personal cost of medical implants that fail.

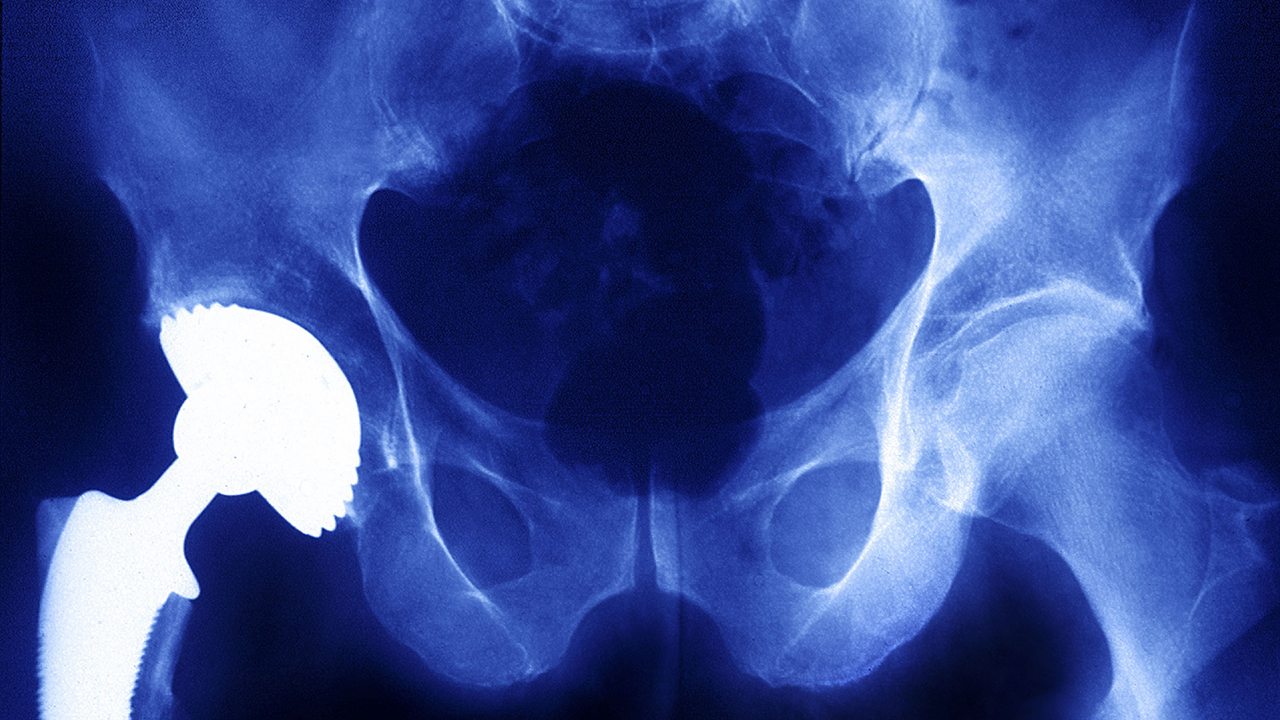

We heard from people with hip implants, pain pumps, ankle implants, spinal cord stimulators, breast implants, heart devices, mesh and more.

En Ju, from South Korea, had a spinal cord stimulator implanted two years ago to help with chronic pain.

She says that she was not told of any risks associated with the device and now when it charges, she feels like her skin does, too.

“Since then, I am also sensitive to the electricity flowing in my body – and my skin gets sweaty,” she said.

We heard from several people affected by multiple devices, including an American with a spinal cord stimulator as well as a hip implant, a French person with a coronary stent and hip implant, and an Australian who received transvaginal mesh and a birth control implant.

Of the more than 3,500 responses shared with ICIJ, most (2,755) were from people who have had an implanted device, or know someone who has.

Valérie, from France, had her birth control device, Essure, removed after suffering “extreme” fatigue, “unbearable” arm and hip pain, memory loss and sight problems for four years.

She said her gynecologist “always denied a link between my health and the implant” but after media reports, she decided to get it removed. Even after her operation, she continued to have pain in her hips and has been unable to play any sport

Irishman David is still prevented by pain from sitting upright at work 14-months after getting a hernia mesh, despite taking “an anti-inflammatory smoothie each day.”

“I’m not able to do any physical activities since the operation. This hasn’t improved overtime which is hard to take as I used to regularly play soccer and to go the gym,” he said.

We translated the survey into nine languages and shared it with our network of media partners around the world.

People living in 50 countries responded. Our survey showed that many people traveled from their homelands to other countries for their operation.

After receiving several responses from French women, reporters from our Tunisian partner Inkyfada teamed up with journalists from Le Monde in France. What they discovered was a number of women traveling from France to Tunisia for surgery.

“We finally managed to find testimonials by posting a public appeal for information in specific Facebook groups, on the particular issue of medical tourism and breast implants,” Malek Khadhraoui, director of Inkyfada, said.

“This information furthered our investigation into the medical tourism industry in Tunisia and the many risks that it entails.”

Our data also revealed there are Australians traveling to Thailand, and Canadians to China, Brazil, South Korea and Burundi, for their implant operations.

The callout gave investigative reporters a chance to speak directly with their audience. And although responses were dominated by English and French speakers (91%), we also received them in Japanese, Korean and Dutch.

“I believe the callout encouraged the Japanese audience, who are extremely shy and hesitant to speak out, to have their say,” Yasuomi Sawa, senior reporter at Japan’s Kyodo News, told ICIJ.

Sawa, who worked on the Implant Files, said the callout became an important part of their reporting which gave journalists a unique opportunity to get “precious first-hand voices, including whistleblowers.”

“We could publish important stories with vivid insight about the aesthetic surgery industry.”

In total, more than 200 people wrote to tell us about their experience in the healthcare and medical device industry.

Though a much smaller number, they often proved fruitful contacts for our partners, including for Newstapa, in South Korea, who said it was a “crucial” way for them to make contact with importance sources.

We did a follow-up story that uncovered an alleged “kickback scheme by one of the major multinational device makers,” said Wooram Hong, Newstapa reporter.

“After our story, the Fair Trade Commission and the police both opened investigations.”

Another tip, sent by an anonymous whistleblower, enabled our Spanish partners at El Confidencial to uncover evidence of conflict of interest in medical trials at a leading university.

“We investigated [the tip] and finally we published this clear example of malpractice,” Marcos García Rey said.

The thousands of responses to our survey reinforced what we found during our yearlong investigation: that patients are often implanted with medical devices without knowing all the dangers.

More than 1,400 responses were from people who were either living with, or had previously had, breast implants. Of those responses, just 1% said they were properly warned about any potential long-term dangers. As we reported last year, doctors have a duty to alert patients to potential hazards of a treatment.

Fernanda, a breast implant patient from Brazil, told us she hadn’t had a “normal life” since her 2014 operation. “I’ve had hair loss, ankle pain, backaches… tiredness, fatigue.”

“I am finished,” she wrote.

ICIJ would like to thank all of its media partners from the Implant Files who helped with translations, editing, sharing the callout, replying to patients and reporting on what they found. Of course, none of this would be possible without the more than 3,500 people who took the time to reply to our survey. Thank you!