The Cayman Islands, one of the world’s most important offshore tax and secrecy havens, has said it will slowly move towards making public the names of individuals behind tens of thousands of companies registered in the territory.

But the three-island Caribbean jurisdiction, home to almost 65,000 people, insisted it would not be rushed. It will first watch as European Union countries make good on their commitment to introduce corporate ownership registries by 2023. In a statement, the Cayman government said: “We will advance legislation to introduce public registers of beneficial ownership information when that occurs.”

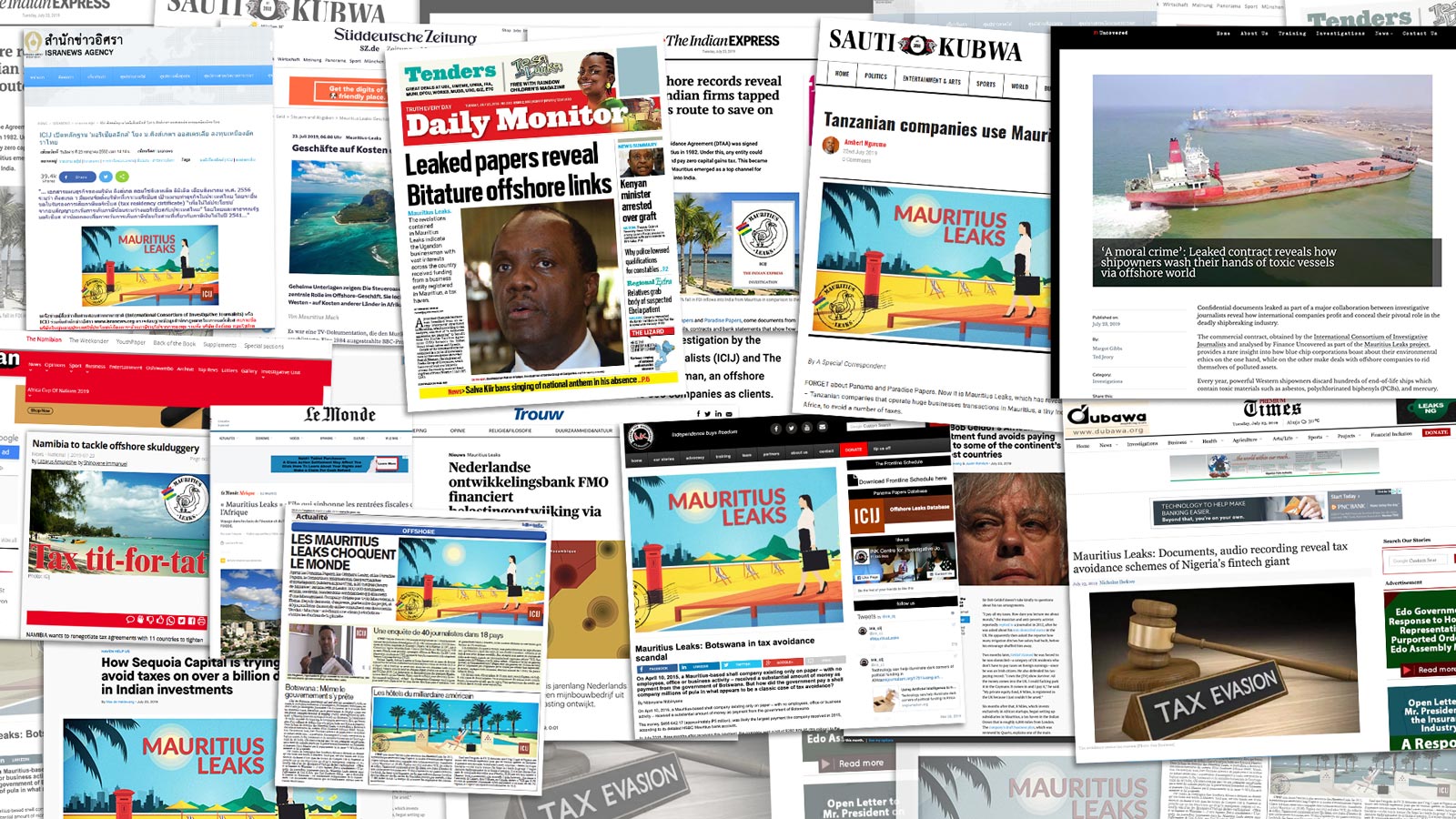

Pressure on tax havens to abandon corporate secrecy follows several large data leaks that have thrown a rare spotlight on the inner workings of the offshore industry — exposed, in large part, by the Offshore Leaks, Panama Papers and Paradise Papers investigations from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. As a result, jurisdictions like Cayman have been forced to consider public registries that show who ultimately owns all locally registered companies.

In the absence of such measures, corporate secrecy can be exploited by criminals ranging from drug cartels and sanction-busters to tax evaders and people traffickers. At the same time, small, remote jurisdictions can gain economic advantage by tailoring their laws to cater to wealthy corporations and individuals looking to set up shell companies and cloak their business affairs in secrecy.

In the past, Cayman Islands companies featured in some of the world’s biggest corporate scandals, and the territory was once a regional hotspot for drug smuggling and money laundering.

More recently, the islands’ offshore economy has focused on hedge fund management and insurance, though it came under fire in 2009 when Barack Obama, then a U.S. presidential candidate, described Ugland House, an office block where tens of thousands of Cayman companies were registered, as the “biggest tax scam in the world.”

Cayman’s latest transparency pledge was immediately welcomed by anti-corruption group Global Witness. Senior campaigner Naomi Hirst said: “This commitment from the Cayman Islands to reveal the real people behind companies on their shores shows how company transparency is now the global standard in financial integrity.”

The move comes almost 18 months after backbench members of parliament in the United Kingdom unexpectedly out-maneuvered the British government, passing a law that would eventually force corporate transparency on Britain’s overseas territories — 14 former colonies including leading tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands, Gibraltar and the Cayman Islands.

Each of the U.K.’s overseas territories operates as an almost entirely self-governing jurisdiction. Britain only rarely uses its powers to intervene, known as “orders in council.” In 1991, it did so to outlaw the death penalty, and in 2000, it acted again, decriminalizing homosexual acts.

British backbench members of parliament had hoped their 2018 law, which committed the government to another order in council, would force U.K. overseas territories to introduce public registries of ownership by 2020, but at the end of last year, British foreign office minister Tariq Ahmad explained that the government would not, in fact, require the measures to be in place until 2023.

“[Overseas territories will] be obligated to produce an operational public register by 2023. That is the current timetable,” he said in December.

However, the latest comments from Cayman Islands suggest the Caribbean jurisdiction may once again be looking to push back on this deadline.

Together with other overseas territories, Cayman reacted angrily to moves by British parliamentarians to intervene in its affairs last year. At the time, Alden McLaughlin, Cayman Islands premier, said he was considering a legal challenge to the legislation.

“We don’t want to wind up in a situation where every time the U.K. parliament disagrees with a decision in one of the territories, it has the power to legislate for us,” he said. “Then it is not just the issue of public registries, it is not just the future of our financial industry that is at risk, it is our very existence.”

Lorna Smith, then executive director of BVI Finance, an offshore industry trade group, said the U.K.’s move “smacks of colonialism.”

Defending their existing arrangements for guarding against corporate abuse and criminality, many overseas territories said they already held information on who secretly owned companies, and shared the details with overseas tax investigators and law enforcement when requested to do so.

A report published by the French parliament last week noted that following Panama Papers revelations in 2016, tax officials in France had started a large number of investigations, issuing 307 requests for assistance with their inquiries, 196 of which were sent to the BVI. However, the report noted, three years later, 176 requests remained unanswered.