West Africa was high on our need-to-do list when the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists launched the Panama Papers in April 2016.

Even though there were more than 370 journalists from close to 80 countries working together, sharing ideas and offering a helping hand, there were still many parts of the world that demanded more coverage.

Since then, ICIJ has immersed itself in soliciting, training and working with journalists from new countries – including those in West Africa. It’s part of what we do: bringing journalists together and creating cross-border reporting partnerships to help shine a light in every corner of every continent of the world.

In the Panama Papers, ICIJ previously had found and reported that companies and individuals from 52 of Africa’s 54 countries were in the data. Nearly every country had a potential story.

So we had a hunch that West Africa, a family of 15 countries that speak French, English, Portuguese and hundreds of local languages, would have plenty of secrets to reveal.

ICIJ teamed up late last year with a regional nonprofit organization that specializes in producing West African investigations, the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Journalism (Cenozo).

The organization is named after one of West Africa’s most celebrated reporters, Burkina Faso’s Norbert Zongo, who was killed in unresolved circumstances.

In February, ICIJ and Cenozo held an event in Senegal. We helped journalists every step of the way, from setting them up with email encryption so we could communicate securely, to tracking down documents in the United Kingdom, the United States, Italy and elsewhere that had a connection to West Africa. When needed, we made calls from the United States to politicians who had previously refused to speak with local African reporters.

This investigation uses ICIJ’s collaborative technology so journalists can search for stories of public interest in nearly 30 million records that come from four different data sets: Offshore Leaks, Swiss Leaks, Panama Papers and Paradise Papers.

West Africa is too important to be left out of this reporting because the impact of tax avoidance, financial crime and corruption there is huge. Gross domestic product per capita would be 15 percent higher across Africa if money had not been siphoned from the continent, experts say.

The region is one of the least developed in the world. In 2016, it had the slowest growth of any of Africa’s five regions, according to the African Development Bank.

Untraceable money piped out of West Africa accounts for more than one-third of all the money that leaves the entire African continent each year, according to the United Nations.

ICIJ wanted to help bring more of West Africa’s offshore stories to light, and we knew that local knowledge and expertise would be key.

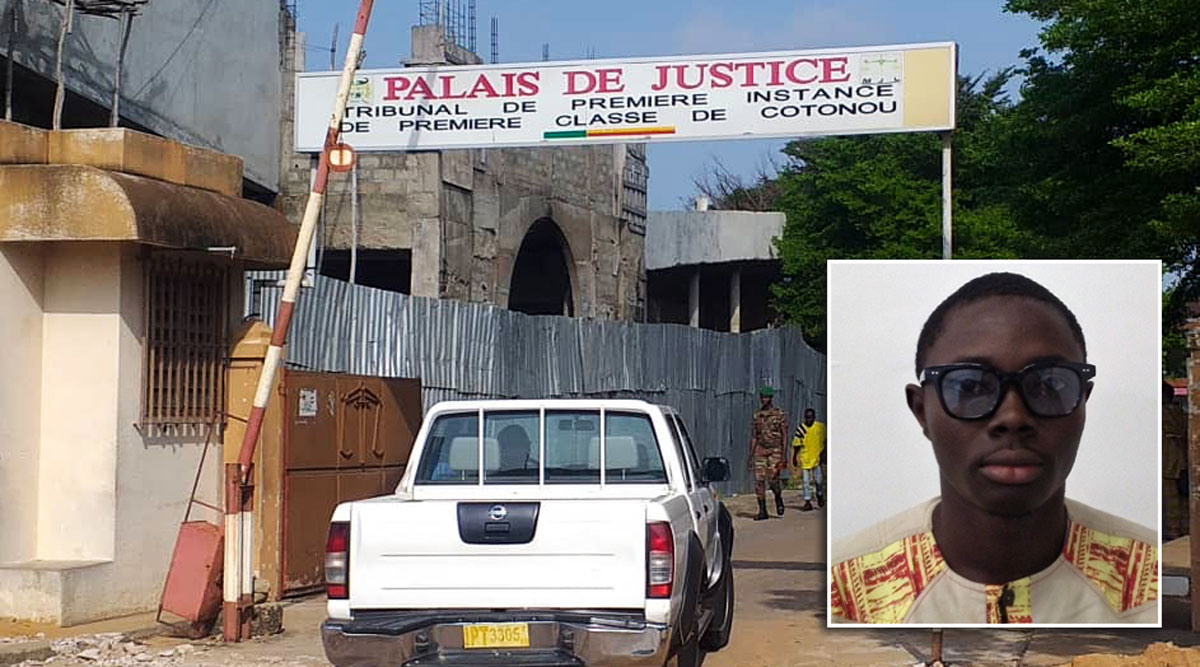

But challenges to investigative journalism in West Africa, as in many countries in Africa, are daunting. Journalists earn little money, work under extreme pressure and are often disconnected from the wider world.

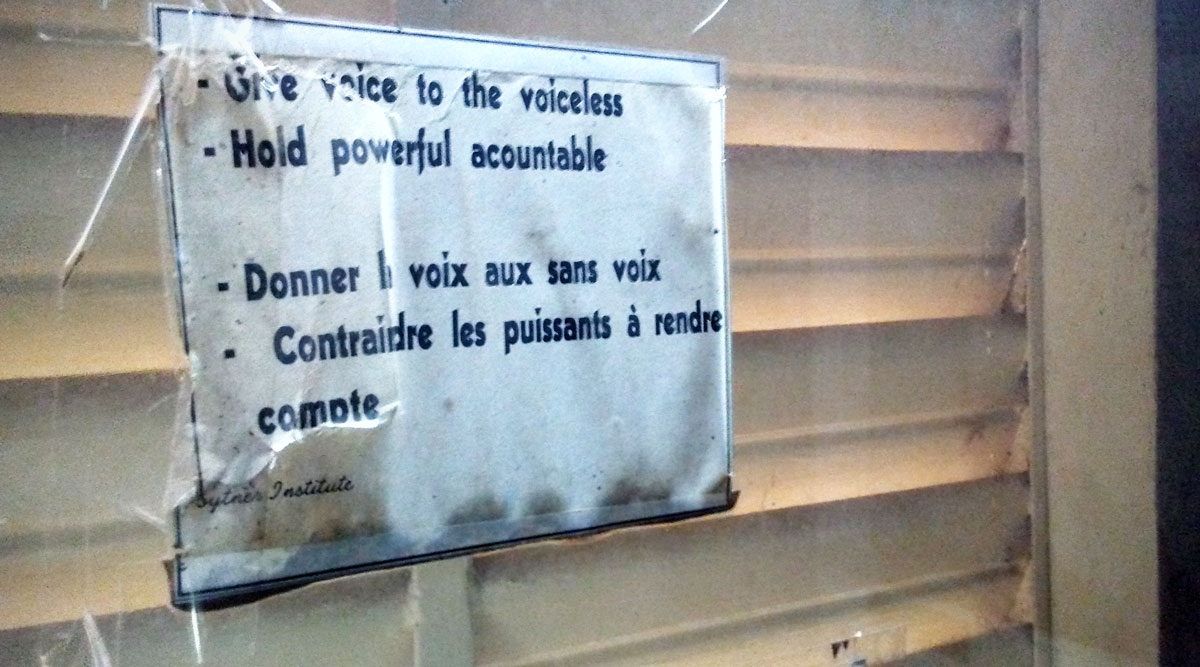

Telling stories about any country’s most powerful individuals and companies is never easy. But it’s a lot harder to ignore a global community of reporters than it is one investigative journalist working alone.

That’s the power of collaboration.

It is part of ICIJ’s mission that no stone is unturned in the pursuit of truth and that no investigative journalist, if they have the passion and have the skills, works alone. That’s why we had to be there.