Last week Apple said it would bring hundreds of billions of dollars in offshore cash – largely profits recorded outside of America, accumulated over the past 12 years – back to the United States, where the company would pay a record-breaking $38 billion in tax as a result.

Explaining the move, chief executive Tim Cook said that he had a “deep sense of responsibility to give back to our country and the people who help make [Apple’s] success possible.”

But how good a corporate citizen is Apple really being? And does this arrangement represent good value for ordinary Americans? Let’s look a bit closer at the context.

Apple’s big move comes as the ink dries on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed by President Donald Trump last month. This legislation contains sweeping changes, the ramifications of which are set to reverberate around the world this year and into the future.

For now, though, we’re interested in just one aspect of the new law: a crackdown on stockpiles of foreign profits, made by U.S. multinationals but parked in offshore subsidiary companies in order to avoid U.S. tax.

For years, multinationals’ foreign profits – profits that would have be taxed at 35 percent if they were brought home to the United States (subject to an adjustment for any foreign taxes already incurred) – were instead stashed abroad. By storing up these earnings in foreign subsidiaries, multinationals have been able to defer U.S. taxes due on such profits.

And, as American multinationals also grew increasingly adept at avoiding taxes in overseas markets, the benefits of parking profits outside America – thus avoiding U.S. taxes – produced even larger savings.

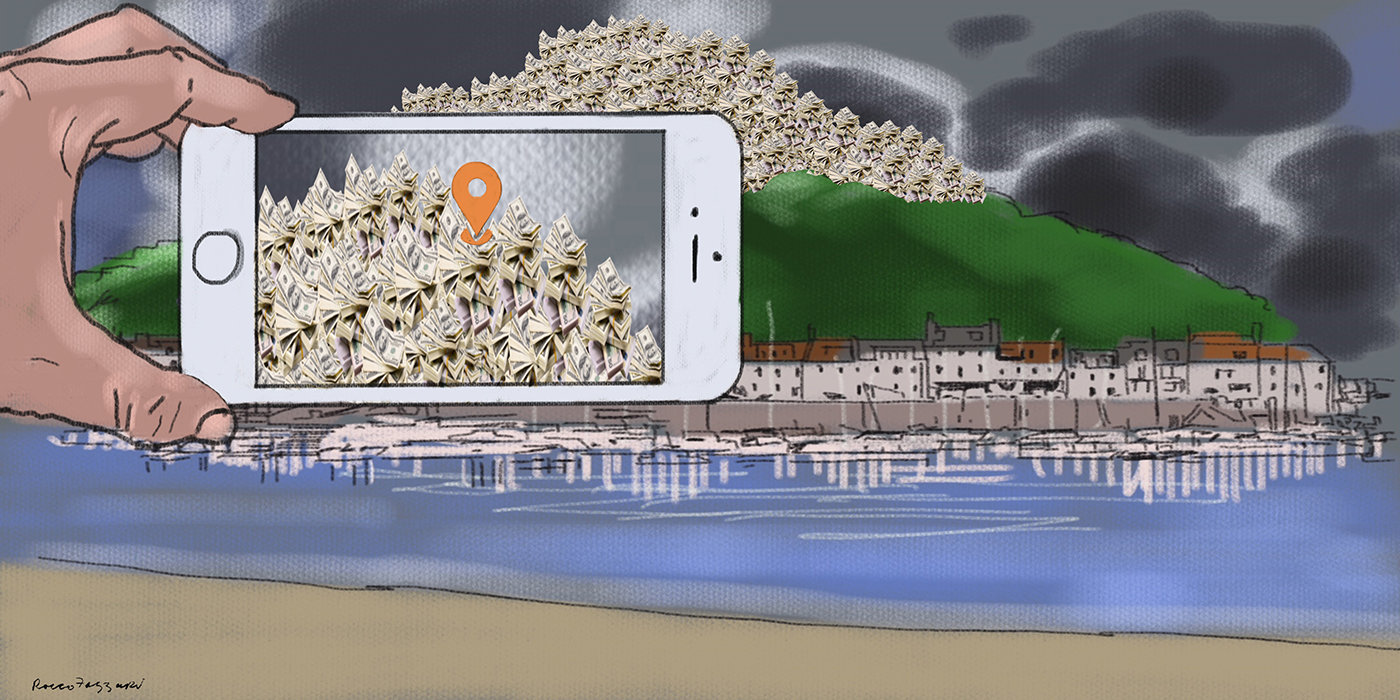

In the end, many big corporations were achieving astonishingly low worldwide tax rates and amassing mountains of cash offshore. Some estimates suggest as much as $2.8 trillion has been locked in this offshore limbo. And no multinational has been better at the avoidance game than Apple.

At last count, the iPhone-maker held offshore cash reserves of $252 billion – equivalent to more than a quarter of its nearly $1 trillion market capitalization.

Under normal circumstances, these surplus profits would have been repatriated to the United States and returned to shareholders in stock buybacks and dividends. But such an option has not been available to Apple – at least, not without an accompanying tax bill of close to 35 percent.

Wall Street analysts have for years described the iPhone-maker’s offshore cash as “trapped.”

While the conundrum of what to do with these earnings was a nice dilemma to have, it has nevertheless thrown a spotlight on how dysfunctional U.S. tax rules have become.

To the outside world, it is baffling that American tax authorities allow Apple to claim the majority of its profits are generated outside the United States and that such earnings can therefore be perpetually held beyond the reach of the Internal Revenue Service.

Surely, almost all the value in Apple is created in Cupertino, California. It makes no sense for the majority of profits not to be recorded there too.

Last fall, as they drew up the Tax Cuts and Jobs Bill, Republicans in Congress were determined to repatriate the mountains of cash that corporate America’s top tax avoiders had amassed.

And doing so was simple. The new legislation would simply extend the reach of U.S. tax authorities, giving them taxing rights over past years’ foreign profits on which multinationals had, up to now, been able to claim tax deferrals.

A discounted tax rate for repatriated profits

But the lawmakers did not stop there. Republicans decided that multinationals should not be forced to dismantle offshore cash reserves without recompense. There was to be a special, discounted tax rate for repatriated profits.

Why is far from clear. As many eminent tax practitioners and academics have pointed out, a reduced rate effectively rewards years of aggressive tax avoidance.

But the perceived need to offer America’s largest and most profitable companies a retroactive saving on their tax liabilities was built on two ideas that seemed to go unchallenged.

The first was that without the incentive of a discounted tax rate, powerful multinationals could never be persuaded to bring their offshore cash back. The second was that taxing the tsunami of repatriated earnings at a reduced rate would create more U.S. jobs.

Here is how Apple chief executive Tim Cook put it in 2013, when he testified before a U.S. Senate committee:

Apple has been pressing Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill for a “reasonable” repatriation tax rate for some years.

And, as decision time approached in 2017, the iPhone-maker raised the amount it was spending on U.S. lobbying.

In the fall of 2017, as Republicans got down to the nitty gritty details of the bill, they had to decide what “reasonable” meant. In October, Trump’s chief economic adviser Gary Cohn – one of the so-called “Big Six” figures in Washington charged with thrashing out a legislative proposal – told Fox News the rate would be in the “10 percent range.”

By early November, bills emerged from the House and Senate proposing a repatriation tax rate of 12 percent and 10 percent respectively.

But as these figures began circulating, Republicans found they faced two problems. First, some of their congressional allies were growing uneasy about the impact of mega giveaways in the bill would likely have on the government’s borrowing.

Some projections suggested tax breaks in the bill were so generous that no resulting boost to the economy could ever hope to generate enough extra tax receipts to fill the hole left behind in government income – especially in the first few years.

The second issue for lawmakers was that polls showed that the wider public – including many blue-collar workers, core to Trump’s base — simply didn’t believe that tax giveaways to big corporations would end up benefiting them.

Paradise Papers expose Apple’s island hop

It was against this backdrop that the ICIJ and its media partners published a detailed investigation into the tax affairs of Apple based on information contained in a cache of millions of confidential documents known as the Paradise Papers.

The investigation, a version of which was also published prominently in the New York Times, exposed how Apple had secretly reconfigured a cluster of Irish subsidiaries in 2015 – with the help of the tax haven Jersey – to unlock huge tax breaks for the iPhone-maker’s non-U.S. business.

Since these new arrangements had been put in place, the ICIJ research found, Apple’s offshore cash pile had almost doubled to $252 billion.

Later the same month, the tone of the Republican tax reform debate around multinationals changed. As the bills progressed through Congress, both the House and Senate hiked their proposals for the repatriation tax rate until it was eventually signed into law at 15.5 percent. This was still a major tax giveaway but a rate more than 50 percent above that proposed by Republican lawmakers months earlier.

Had the rate been set at that 10 percent rate, the repatriation tax owed that Apple announced last week would have been around $25 billion, not the $38 billion announced – a difference of $13 billion.

While some in Cupertino may feel Apple missed out on the big reward for returning its profits, investors remain delighted. In fact, the company’s stock is up by almost two-thirds since Trump won the White House.

In the end, the repatriation tax charge – for so long an uncertainty hanging over Apple stock – looks so neat it could have been scripted by Cook himself. In fact, the company’s latest balance sheet shows the iPhone-maker has already built up $36 billion in accounting provisions for tax it had expected to have to pay on its foreign earnings.

As a result, the eventual payment of Apple’s record-breaking repatriation tax bill will hardly impact the company’s 2018 earnings per share performance.

It remains to be seen, however, what Apple does with its repatriated cash. Last week, Cook was talking loudly about a huge program of investment and thousands of new U.S. jobs. And this was a message that clearly delighted the president:

I promised that my policies would allow companies like Apple to bring massive amounts of money back to the United States. Great to see Apple follow through as a result of TAX CUTS. Huge win for American workers and the USA! https://t.co/OwXVUyLOb1

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 17, 2018

This is the “jobs” half of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. But is Apple’s announcement as exciting as it sounds?

While Apple will, of course, continue to invest in jobs, research and innovation, it seems unlikely that Cook – however grateful he must be for outcome tax reform – will bow to some of Trump’s more outlandish job-creation demands.

In the heat of his election campaign, the president had promised on Twitter “We’re going to get Apple to start building their damn computers and things in this country, instead of in other countries.”

Wall Street is likely to have other ideas. Cook would likely face a shareholder revolt if the vast majority of repatriated cash is not promptly returned to investors through share buybacks and dividends.