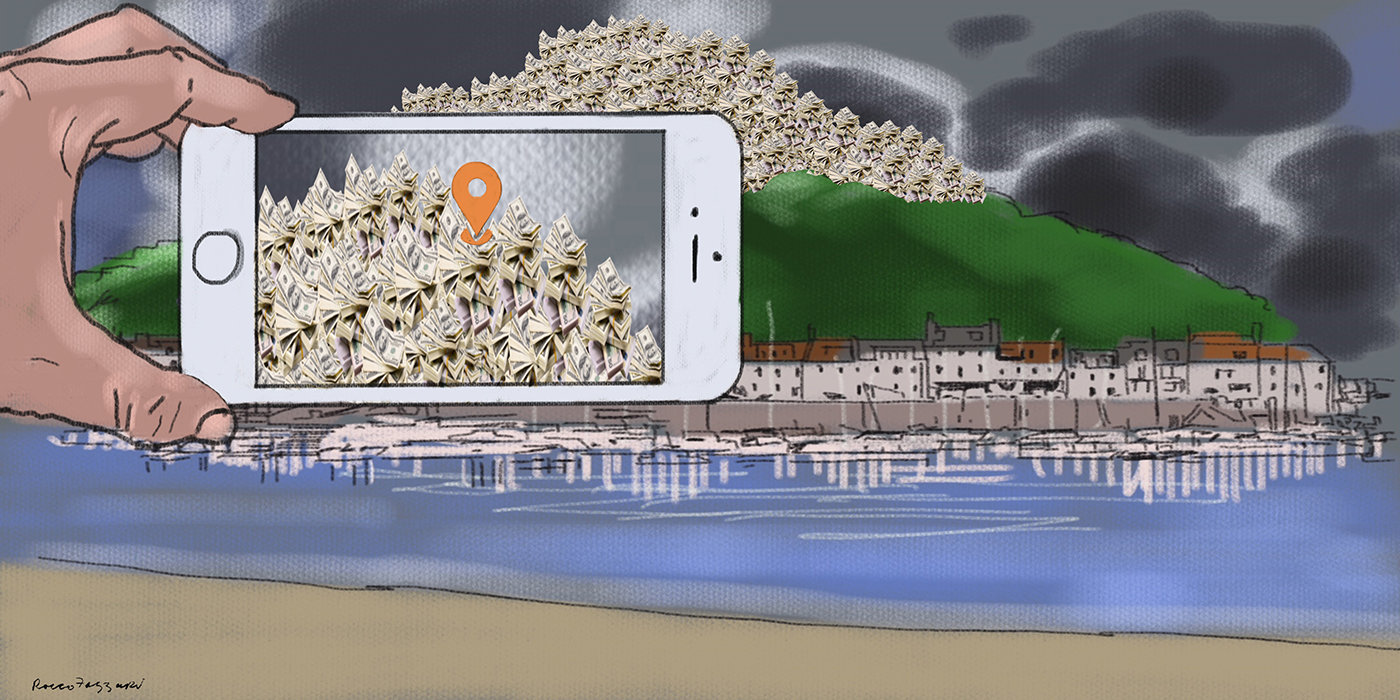

PARADISE PAPERS

Apple dodges $15b tax bill in EU court appeal

Europe’s second-highest court has overturned a ruling by the European Commission in a major blow for attempts to crack down on tax corporate tax avoidance.

Apple does not have to pay $14.8 billion in Irish back taxes, Europe’s second highest court has ruled, in a major blow for attempts to crackdown on tax avoidance by global corporations.

The European Commission ruled four years ago that the additional taxes had to be paid, saying the tech giant had benefited from illegal state aid after Ireland promised it favorable tax treatment in a private agreement known as a “tax ruling.”

But Apple and Ireland today won an appeal that annuls the finding that the tech giant’s international tax arrangements violated Europe Union competition laws and amounted to illegal state aid.

The General Court of the EU found that the Commission was “wrong to declare” Apple “had been granted selective economic advantage and, by extension, state aid.”

European competition commissioner Margrethe Vestage is expected to take the case to the European Court of Justice on appeal.

The Apple case is the largest in a series of Vestager state aid cases focused on tax rulings handed to multinational corporations by some of the smaller EU member states — particularly Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.

For decades, these countries have aggressively tailored their tax policies to appeal to multinational corporations seeking to avoid taxes across Europe. As a bloc, the European Union has struggled to stamp out this predatory behavior, so Vestager has been attempting to tackle the most egregious cases of tax avoidance using competition law.

Other European tax rulings she has targeted include those granted to Starbucks, Fiat, and Ikea.

Last year, Vestager opened two further state aid investigations after reporting by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its partners.

The first focused on a tax ruling granted to Nike in the Netherlands, revealed in ICIJ’s 2017 Paradise Papers investigation; the second concerned a ruling Luxembourg gave to Finnish packaging firm Huhtamäki, which featured in ICIJ’s 2014 Lux Leaks investigation.

The Apple case stems from tax rulings granted in 1991 and 2007. Following these agreements, Apple was able to channel up to two-thirds of its global profits into subsidiary companies, registered in Ireland, that paid almost no tax.

Apple’s Irish tax arrangements first attracted criticism in 2013, when the U.S. Senate’s permanent subcommittee on investigations looked into the matter, publishing pages of financial data and testimony.

At the end of a six-hour hearing, committee chair Carl Levin (D-Mich.) summed up the findings. “You shifted that golden goose to Ireland,” he told Apple chief executive Tim Cook. “You shifted it to three companies that do not pay taxes in Ireland … These are the crown jewels of Apple Inc … Folks, it’s not right.”

In earlier testimony, Cook had told senators: “There is no [profit] shifting going on that I see at all,” he said. “Apple has real operations in real places, with Apple employees selling real products to real customers. We pay all the taxes we owe – every single dollar … We don’t depend on tax gimmicks.” Cook’s claim was later repeated by the Irish government.

In Europe, Vestager used findings from the U.S. Senate investigation to launch her own probe, examining whether Ireland’s generous tax treatment of Apple companies had breached EU fair competition laws.

The Commission’s conclusion — overturned today — found that Apple should not have been allowed to allocate lucrative intellectual property licenses for iPhones, laptops and other devices to certain parts of Irish subsidiary companies that were not subject to tax in Ireland.

That conclusion, the General Court has ruled, was “incorrect.”

Welcoming the court’s decision, the Irish finance ministry said: “Ireland has always been clear that there was no special treatment provided to the two Apple [subsidiary] companies… The correct amount of Irish tax was charged in line with normal Irish taxation rules.”

The finance spokesperson for Ireland’s main opposition Sinn Fein party, Pearse Doherty, criticized the ministry’s statement. “Regardless of the judgement today, people know that what happened here was morally wrong in terms of tax fairness and that does heap pressure and draws undue attention to the fact that we have a competitive tax rate,” he told RTE, the national broadcaster.

Responding to the court’s decision, Vestager said the Commission would study it fully, but insisted she would “continue to look at aggressive tax planning measures under EU state aid rules.”

This is so wrong, in so many ways.

Ireland is a major #taxhaven causing losses to other countries in the world.

In times of COVID-19 every single EUR in government revenue is crucial.

But let’s protect the interests of one of the biggest multinationals. https://t.co/HG5JOdnAs3

— Johan Bernardo Langerock (@JohanLangerock) July 15, 2020

Apple said: “This case was not about how much tax we pay, but where we are required to pay it. Changes in how a multinational company’s income tax payments are split between different countries require a global solution, and Apple encourages this work to continue.”

Five months after the U.S. Senate hearings on Apple in 2013, Ireland bowed to international pressure and promised a crackdown on multinationals using Irish-registered subsidiary companies that claimed almost all of their income was not subject to taxes in Ireland or anywhere else in the world.

However, in 2017, as part of ICIJ’s Paradise Papers, journalists revealed how Apple secretly reorganized its Irish companies in a way that allowed its tax advantages to continue uninterrupted.

Earlier in 2017, reporting by ICIJ partners showed how Ireland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg regularly used their veto powers to block reform of EU-wide efforts to set common standards to curb tax avoidance by multinational corporations.